Two Observations on the Supervision and Regulation Report

Plus: a white paper on national bank authority to issue stablecoins

Supervision and Regulation Report

On Thursday the Federal Reserve Board released its semi-annual Supervision and Regulation Report. Among other things, the report includes a series of observations relating to the progress of large financial institutions (LFIs)1 in remediating previously identified supervisory deficiencies. As summarized in the introduction to the report:

Most firms maintained satisfactory supervisory ratings, and the number of unresolved supervisory findings has been declining; however, some findings are taking longer than expected to remediate, especially for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and other large banks.

In particular, although most LFIs are generally meeting supervisory expectations with respect to capital and liquidity…

many of these firms have multiple unresolved supervisory findings on governance and controls that are under remediation, including weaknesses in operational resilience, information technology, third-party risk management, and Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money laundering compliance.

The picture is generally the same for foreign banks with operations in the United States, but with AML issues also added to the mix:

Deficiencies for foreign firms are generally consistent with those highlighted for domestic institutions; however, a key difference is foreign firms’ compliance with Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money laundering expectations. As noted in previous reports, some foreign firms have a number of Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money-laundering findings and enforcement actions. In some cases, these issues result in less-than-satisfactory supervisory ratings for governance and controls.

At least one advocacy group has interpreted these and other statements in the report as marking the end of “hands off” supervision by the Board and signaling a clear change in Board priorities. I tend to think this overstates the degree to which supervision was previously hands off, and in any case I am not sure the timing completely works if the argument is that this was a top-down driven change.2

But regardless of your views on that specific question, the passages quoted above are still notable for at least two other reasons.

Implicit Firm Specific Commentary

The report does not identify any firm by name. Even so, it is tough to read the Board’s description of its displeasure with the pace at which firms are remediating weaknesses without thinking of the WSJ reporting earlier this year that “Federal Reserve officials have … demand[ed] to see more progress” from Citigroup in addressing the issues identified in a 2020 consent order.

Notable in this regard is the Board’s commentary on its supervisory expectations relating to previously identified technology infrastructure, data and operational resilience issues (i.e., many of the same issues cited by the Board in its consent order with Citigroup3):

Remediation of issues around technology infrastructure, data, and operational resilience often take longer to address than issues in other business and risk-management areas. Many require a firm to develop a multiyear remediation plan. When reviewing these plans, supervisors expect firms to make the needed investments in systems and risk management to ensure adequate controls. Supervisors also expect firms to remediate findings in a timely manner.

At a high level, this is not too different from what Citigroup’s own management has been saying publicly about the need to make investments and how long shareholders should expect the process to take.4 It is the reference in the final sentence to a "timely manner" that may be where the difference of opinion comes in.

To be clear, the Board’s comments in the report are obviously not directed only at Citigroup. There are other domestic firms to which some of the same comments equally apply. Similarly for foreign banks, the Board’s observation that certain firms continue to have AML weaknesses in their U.S. operations could reasonably be read as applying to any one of a number of firms.

Bigger Picture: The LFI Rating System

The Federal Reserve Board evaluates LFIs under a supervisory rating system that assigns individual ratings for three components: capital planning and positions, liquidity risk management and positions, and governance and controls. Ratings for each component are assigned on a four-point non-numeric scale ranging from to best worst: Broadly Meets Expectations, Conditionally Meets Expectations, Deficient-1 and Deficient-2.

A firm must be rated either Broadly Meets Expectations or Conditionally Meets Expectations on all three components to be regarded as in satisfactory condition. This matters because firms that are not in satisfactory condition may become subject to formal enforcement actions and may face restrictions on their ability to make acquisitions or to engage in new activities.

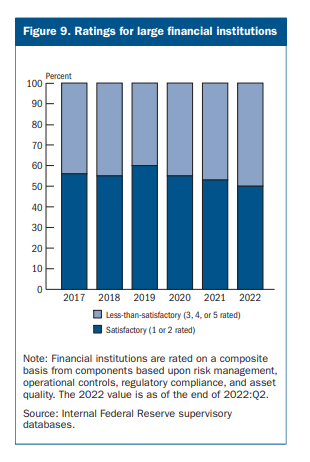

Per the latest Supervision and Regulation report, “just under half” of LFIs are in satisfactory condition.

On its own this number is not all that notable and not much changed compared to previous years.5 But when read alongside the Board’s observations elsewhere in the report that certain supervisory findings have taken longer than expected to remediate, the lack of year-over-year change may raise an interesting question about how the Board is applying, or intends to apply, its LFI rating system.

When it adopted the LFI rating system, the Board stated that the length of time taken to remediate supervisory findings is an important consideration in assigning supervisory ratings. In fact, as first proposed the Conditionally Meets Expectations rating (then referred to as Satisfactory Watch), would have been explicitly time limited.6

In the proposed LFI rating system, the second highest rating category was “Satisfactory Watch.” … The preamble to the proposal noted that the “Satisfactory Watch” rating was not intended to be used for a prolonged period; rather, firms would have had a specified timeframe to fully resolve issues leading to that rating (as is the case with all supervisory issues), but generally no longer than 18 months.

Commenters argued, however, that this approach was inappropriate, and the Board ultimately agreed to move away from a fixed timeline.

Several commenters noted that many supervisory issues take longer than 18 months to resolve, and that resolution of certain issues requires substantial infrastructure investment and changes in processes and controls. …

… unlike the proposal, the final ratings framework does not establish a fixed timeline for how long a firm can be rated “Conditionally Meets Expectations.” Instead, the final ratings framework reflects an understanding that timelines will be issues-specific, noting that the Federal Reserve will work with the firm to develop an appropriate timeframe during which the firm would be expected to resolve each supervisory issue leading to the “Conditionally Meets Expectations” rating. Further, the final ratings framework reflects an understanding that completion and validation of remediation activities for selected supervisory issues—such as those involving information technology modifications—will require an extended time horizon. …

At the same time, even though the specific reference to an 18-month timeframe was removed, the Board continued to make clear that firms would not be permitted to linger in the Conditionally Meets Expectations category. The Board also signaled that failure to timely resolve issues would likely result in a downgrade to an unsatisfactory rating.

The Federal Reserve does not intend for a firm to be assigned a “Conditionally Meets Expectations” rating for a prolonged period, and will work with the firm to develop an appropriate timeframe to fully resolve the issues leading to the rating assignment and merit upgrade to a “Broadly Meets Expectations” rating. A firm is assigned a “Conditionally Meets Expectations” rating - as opposed to a “Deficient” rating - when it has the ability to resolve these issues through measures that do not require a material change to the firm’s business model or financial profile, or its governance, risk management or internal control structures or practices. Failure to resolve the issues in a timely manner would most likely result in the firm’s downgrade to a “Deficient” rating, since the inability to resolve the issues would indicate that the firm does not possess sufficient financial or operational capabilities to maintain its safety and soundness through a range of conditions.

The latest supervision and regulation report does not provide details as to how many of the firms criticized elsewhere in the report for failing to timely remediate outstanding supervisory issues are rated Conditionally Meets Expectations and how many are already assigned Deficient ratings. If a firm is already in a Deficient category, then in one sense the failure to remediate supervisory issues matters relatively less, as the firms in question are already in unsatisfactory condition and are already subject to the consequences that comes with that status.7

Assuming that at least some firms described in the report are still rated Conditionally Meets Expectations, however, this may set up a few consequential firm-specific decisions for the Board to make in the coming supervisory cycle. If so, the Board may wind up facing criticism whatever it decides to do.

Those that believe supervision has previously been too weak may argue that if the Board meant what it said about firms not being permitted to remain in the Conditionally Meets Expectations category for a prolonged period, and if a firm has continued to fail to meet the Board’s expectations with respect to remediation timelines, then the Board’s ratings system suggests that, at a minimum, downgrades to Deficient status will be in order.

On the other hand, those that believe supervision too often tends toward being arbitrary or unfair may argue that if the Board does follow through with ratings downgrades then the Board would be backsliding on some of the statements it made when adopting the LFI rating system about working with firms to develop timelines and recognizing that certain issues will require longer time horizons.

Of course, these views are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and the most appropriate approach may vary from firm to firm depending on the nature of the supervisory findings in question. The need to be fair and consistent while also taking into account genuine firm-specific differences is a key tension inherent in supervision.

Whichever way the questions get resolved, because firm ratings are confidential supervisory information, the public may never get a clear answer on what the Board decided to do. Except, that is, to the extent the public can divine it by looking to the data the Board chooses to provide in future supervision and regulation reports.

The Clearing House White Paper on National Bank Authority to Issue Stablecoins

The Clearing House has published a white paper authored by a prominent law firm arguing that national banks possess the legal authority to issue stablecoins and engage in related activities. This is relevant to, among other things, the OCC’s ongoing evaluation of whether national banks may participate in the USDF Consortium, discussed here and elsewhere recently. Moreover, as the white paper points out, to the extent that national banks have this authority, many state banks may have the same authority by virtue of state parity or wild card statutes which permit state-chartered banks to engage in the same activities in which national banks may engage.

The full paper is worth reading and for whatever my opinion is worth I think it is clearly correct on the authority question. More interesting to me was the discussion in the white paper on a few other issues, two of which I’ll briefly highlight here.

Does Glass-Steagall Prohibit Non-Bank Stablecoin Issuance?

The white paper includes a short section devoted to Section 21(a)(2) of the Glass-Steagall Act, a provision still in effect which prohibits firms without banking licenses from engaging “to any extent whatever" in the business of receiving deposits. The authors argue that, although Section 21(a)(2) does not define deposits, if a stablecoin issued by a non-bank is promoted as the equivalent of deposit, “there would be a serious question whether the issuer is in violation” of the statute.8

This is an fun topic for those who like this sort of thing, and if you are interested in a more detailed treatment I would start by reading this 2021 note from Professors Howell Jackson and Morgan Ricks. Note, though, that as other authors have pointed out, one obstacle to applying Section 21(a) in this way is that it may require revisiting or at least cabining certain MMF-related interpretations issued by the DOJ in the 1970s.

I mention this not out of any sort of pretense to being able to resolve the question here, but instead just to note another instance of the strange alliances sometimes produced by crypto regulation or the lack thereof.9

Does Bank Issuance of Stablecoins Implicate the Volcker Rule?

Surprisingly, the white paper includes a section arguing that issuance of digitized deposits and related activities should not implicate the Volcker Rule because such digitized deposits are not securities or other financial instruments covered by the rule and, in any case, are not held for a bank’s “trading account” as that term of art is used in the Volcker Rule.

I say this is surprising not because I disagree with the authors’ conclusions but because it had not even occurred to me that the Volcker Rule could plausibly be implicated by bank stablecoin issuance. To be clear, I mean this not as a criticism of the authors, who are smarter than I am, and I therefore assume this was included for a good reason. Is this a question that has been raised by the OCC or another federal banking regulator?

The Board defines an LFI as a U.S. firm with total consolidated assets of $100 billion or more or a foreign banking organization with combined U.S. assets (i.e., in its U.S. branch and its U.S. subsidiaries) of $100 billion or more.

For example, certain of the content in the report — e.g., the supervisory ratings on page 25, or the “weaknesses” (that is, MRIAs and MRAs) identified by the Board in connection with this year’s stress test as described on page 26 — are likely to have been finalized before the new Vice Chair for Supervision had even assumed the role.

The Board’s press release accompanying the 2020 consent order noted that, “[a]mong other things, [Citigroup] has not taken prompt and effective actions to correct practices previously identified by the Board in the areas of compliance risk management, data quality management, and internal controls.” The OCC brought its own separate enforcement action based on Citibank’s “long-standing failure to establish effective risk management and data governance programs and internal controls.”

For example, on its Q3 earnings call, Citigroup’s CEO offered the following in response to a question about the WSJ report that regulators had pressed for the firm to move faster:

Yeah. We all want things to go faster, both our clients, our shareholders, the management team, regulators, the Board all. So I think we are fully aligned there. Maybe if I take a step back on this one. Transformation is our number one priority. It will be a multiyear journey and prioritizing safety and soundness is a very important global bank is a non-negotiable for all of us. …

We have got a lot to get done. As you can see from the hiring numbers, we have been investing heavily in the talent and the resources that we need. As we have also said, this is not only going to benefit our safety and soundness, but also in terms of our client excellence in delivery, and ultimately, for our shareholders as well…

The table on page 23 of the report suggests there are currently around 44 LFIs (based on the definition in footnote 1 above), meaning that notable changes in percentage from year to year may be driven by a change of supervisory rating for only one or two firms. Note that the LFI rating system is relatively new, and prior to 2019 LFIs were evaluated under a different rating system applicable to a somewhat different group of firms, so the post-2019 data in the Board’s graphic is not necessarily comparable to pre-2019 years.

Unless otherwise noted, the quotes here are from the Board’s adopting release for the final rule implementing the LFI rating system.

Of course, some argue that these consequences are not sufficiently severe, and say that if firms already rated as unsatisfactory are failing to timely remediate outstanding issues then further action, such as forced divestitures, may be appropriate.

A more cynical reader may wonder whether this “serious question” will be or should have been raised in the context of other matters in which this same law firm is now involved.

For others making similar claims to those in the white paper re: Glass-Steagall, see separate arguments from Professor Arthur Wilmarth, former CFTC Chair Timothy Massad, and Todd Phillips and Alex Fredman at the Center for American Progress.