Should There Be Additional Statutory Constraints on the Vice Chair for Supervision?

I am mostly unconvinced. Also, a note on Calcutt v. FDIC.

Today’s post discusses a House bill that probably does not have much chance of becoming law, a Congressional hearing that may not produce much new information, and a legal issue in a case that may ultimately be resolved on other grounds. I am not really giving this post a hard sell, but if that was not enough to deter you please read on.

Today’s House Financial Services Markup

Later this morning the House Financial Services Committee is scheduled to meet to markup various measures, including the “Increasing Financial Regulatory Accountability and Transparency Act.” This bill is an consolidated version of a handful of individual bills that were previously released for discussion in connection with a hearing earlier this month.

As with most Congressional legislation in the current period of divided government, my default assumption is that this is a messaging bill, with slim prospects for becoming law (at least as a whole1). Even so, messaging bills can sometimes be interesting for what they reveal about the thoughts or frustrations of the current majority, and that is the case with a few provisions here.

Limitations on Who Can Be Vice Chair for Supervision

Let’s start with an apparent frustration that to be honest before now I was not aware even existed.

Section 401 of the bill would require that the Federal Reserve Board Vice Chair for Supervision have “demonstrated primary experience working in, or supervising, insured depository institutions, bank holding companies, or savings and loan holding companies.”

On Twitter a few weeks ago I wondered whether the goal of this was to prevent people with purely academic backgrounds from being appointed to the Vice Chair for Supervision role, but as others pointed out this is maybe understating things: the bill text on its face would seem to also make it difficult to appoint, for example, a law firm partner without in-house or banking agency experience, or someone who has spent most of their career in a Congressional committee staff role.

I am puzzled by what is specifically driving this proposal given that, even if you disagree with the policies they pursued or intend to pursue, it is tough to argue that any of the individuals who have previously served or currently serve as Vice Chair for Supervision have not been qualified.2

I guess the answer is that not everyone agrees. In his press release announcing the bill, Rep. Fitzgerald leveled this criticism at Vice Chair for Supervision Barr:

The Vice Chair of Supervision’s cynical attempt to spin the Fed’s supervisory failures in a predetermined report reflects his lack of relevant banking experience

I have questions about the Barr report that I won’t repeat here, but this specific criticism seems off base.

More to the point, even if the criticism rings true to you, it is not clear to me that this proposed new restriction actually would have stopped the President from nominating Mr. Barr? Among other previous experience, Mr. Barr served two stints in the Treasury Department, including from 2009-2010 during which he helped to write the Dodd-Frank Act. Is this “demonstrated primary experience … supervising” financial institutions?3 Reading the statutory provision narrowly, arguably not, but it is the Senate who gets to make the first (and maybe final)4 call on whether to confirm a nominee and thus how narrowly, or not, to read the language.

The proposed requirement that the Vice Chair for Supervision have “demonstrated primary experience” supervising financial institutions seems to me to leave enough room that, like the requirement in the FDI Act that the FDIC have at least one Presidentially-appointed director with state bank supervisory experience, the Senate would be comfortable reading it loosely if they were otherwise happy with the nomination sent to them by the President.

Limitations on What the Vice Chair for Supervision Can Do Without the Full Board

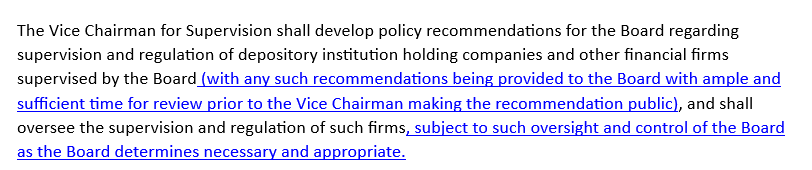

Section 401 of the bill would also make changes to Section 10 of the Federal Reserve Act as redlined below. Compared to the above provision, I think I have better sense of where these are coming from.

The phrase in the parenthetical about “ample and sufficient time for review,” I assume, is being driven by the circumstances surrounding the release of the report into the supervision of SVB. That report, though led by Vice Chair for Supervision Barr and reflecting only his conclusions, was issued via a press release that perhaps gave a different impression, titled as it was “Federal Reserve Board announces the results from the review of the supervision and regulation of Silicon Valley Bank, led by Vice Chair for Supervision Barr.”

Vice Chair for Supervision Barr told Congress last week that his fellow Board members were given the report in advance of its release, but this provision of the bill suggests that some believe the time given was not ample and sufficient.5

As for where the latter change is coming from, I think it is helpful to look at this answer Chair Powell gave at the FOMC press conference earlier this month:

So, on, on the Vice Chair for Supervision, you know, the place to start is, is the statutory role, which is quite unusual. The Vice Chair, it says, shall deploy policy recommendations—“develop policy recommendations for the Board regarding supervision and regulation of depository institution . . . companies . . . , and shall oversee the supervision and regulation of such firms.” So this is Congress establishing a four-year term for someone else on the Board—not, not the Chair—as Vice Chair for Supervision who really gets to set the agenda for supervision and regulation for the Board of Governors. Congress wanted that person to be—to have political accountability for developing that agenda.

So the way it works—the way it has worked in practice for me is, I’ve had a good working relationship. I give my, my counsel, my input privately, and that’s—I offer that. And I have good conversations, and I try to contribute constructively. I respect the authority that Congress has deferred on that person, including working with, with Vice Chair Barr and, and his predecessor. And I think that’s the way it’s supposed to work, and that’s appropriate. I, I believe that’s what the law requires. And, you know—but, but it isn’t—I wouldn’t say it’s a matter of complete deference. It’s more, I have a—I have a role in, in presenting my views and discussing—having an intelligent discussion about what’s going on and why. And, you know, that’s, that’s my input.

But, ultimately, that person does get to set the agenda and gets to take things to the Board of Governors and really, in supervision, has sole authority over supervision.

Maybe Chair Powell is right that, based on the current statute, it was the judgment of Congress that the Vice Chair for Supervision be given “sole authority over supervision” and thus be politically accountable in that way. But that view seems to me to inappropriately reduce the accountability of the Chair (and the rest of the Board) for regulatory policy, in which all of them have a vote. Thus overall although I am skeptical of the need (or efficacy) of the first few proposed changes to the Vice Chair for Supervision role discussed in this post, this last one seems like a reasonable enough idea to me.6

The FRBSF’s “Failure of Supervision”

Also today in Washington, the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability’s Subcommittee on Health Care and Financial Services is scheduled to hold a hearing titled “A Failure of Supervision: Bank Failures and the San Francisco Federal Reserve.”

A hearing about Reserve Banks and the role they should play in supervision seems like a worthwhile topic, and maybe this hearing will produce new details beyond what was produced by the series of House Financial Services and Senate Banking Committee hearings over the past few months.

Perhaps cutting against this, though, is the fact that the announced witnesses for the hearing as of the time of this writing do not actually include anyone from the Federal Reserve Board, the FRBSF or any other Reserve Bank. Instead, the witnesses are set to be:

Jeremy Newell, Senior Fellow, Bank Policy Institute & Founder and Principal, Newell Law Office, PLLC

Michael E. Clements Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment, U.S. Government Accountability Office

Smart folks for sure, but maybe not a recipe for a hearing in which new details about the FRBSF supervision of SVB (or indeed Silvergate Bank) are revealed.7 For better or worse, the excitement (such as it is) may need to be provided by the Subcommittee members.

Calcutt v. FDIC

Harry Calcutt from 2000 to 2013 was the CEO of Northwestern Bank, a <$1 billion asset nonmember bank based in Traverse City, Michigan. By 2009 the bank’s most significant borrowers were “a group of nineteen limited liability companies controlled by the Nielson family” whose businesses involved “development of real estate, holding vacant and developed real estate, and holding oil and gas interests.”8

In 2009, the lending relationship—by then, the Bank’s biggest—began to sour. On September 1 of that year, facing financial difficulties due to the Great Recession, the Entities stopped paying their loans outright. At the time, they owed the Bank $38 million.

A few months later, the parties reached a multistep agreement known as the Bedrock Transaction to bring all of the Entities’ loans current. That agreement stabilized the Nielson lending relationship for the following year. But on September 1, 2010, the Entities again stopped making their loan payments. Another short-term agreement was reached, allowing the Entities to continue servicing their debt for the next few months. But in January 2011, the Entities once more stopped making their loan payments. They have remained in default ever since.

The FDIC investigated the circumstances surrounding these events and brought an enforcement action against Calcutt under Section 8 of the FDI Act, alleging failures to comply with the bank’s internal loan policy; that the bank’s board of directors was misled or misinformed; that Calcutt failed to respond accurately to FDIC inquiries and that there were issues with the bank’s financial statements.

After an intervening Supreme Court decision in an unrelated case that dragged the Calcutt proceedings out for longer than is typical,9 an Administrative Law Judge in April 2020 recommended that Calcutt be made to pay a $150,000 civil money penalty and that he also be prohibited from further work in the banking industry. The FDIC’s board of directors in December 2020 accepted these findings and issued a final order.

Calcutt sought review of the FDIC’s order in the Sixth Circuit. In June 2022, a panel of that court held that, as Calcutt had argued, the FDIC got the law wrong in its 2020 decision. A majority of the panel (Judges Boggs and Griffin), however, then went on to apply what they saw as the correct understanding of the law, determined that Calcutt still lost under that standard, and thus affirmed the FDIC’s decision rather than kicking the case back to the FDIC.

In dissent, Judge Murphy argued this was the wrong thing to do:

If anything, my colleagues’ analysis runs afoul of basic administrative-law principles. When an agency’s decision rests on a collapsed legal foundation, we cannot affirm the decision on the ground that the agency might have reached the right outcome under a correct legal view. We must let the agency apply the proper law in the first instance. See Gonzales v. Thomas, 547 U.S. 183, 186 (2006) (per curiam); SEC v. Chenery Corp., 318 U.S. 80, 88 (1943); Henry J. Friendly, Chenery Revisited: Reflections on Reversal and Remand of Administrative Orders, 1969 Duke L.J. 199, 209–10.

Calcutt then sought Supreme Court review, arguing among other things that the Sixth Circuit’s failure to remand the case to the FDIC warranted summary reversal.10

In its response brief, the Solicitor General on behalf of the FDIC agreed with Calcutt, at least with respect to this narrow point, telling the Court the right move was to send the case back to the FDIC, rather than getting into some of the other grounds for reversal offered by Calcutt.

As to the first question presented, this Court should summarily reverse the judgment below because the court of appeals erred by declining to remand the case to the FDIC Board after it determined that the Board had applied the wrong causation standard. As to the second question presented, review is not warranted. The court of appeals correctly held that petitioner was not entitled to relief on his constitutional challenges to the statutory provisions that address the tenure and removability of FDIC Board members and ALJs. That holding does not conflict with any holding of this Court or another court of appeals. And this case would be an unsuitable vehicle for resolving the second question presented because the Court would have no basis for reaching that question if it agrees with the parties on the first question presented.

Earlier this week in a per curiam opinion the Supreme Court summarily reversed the Sixth Circuit, agreeing with Calcutt and the FDIC that the case should have been remanded.

As both petitioner and the Solicitor General representing respondent agree, the Sixth Circuit should have followed the ordinary remand rule here. That court concluded the FDIC Board had made two legal errors in its opinion. The proper course for the Sixth Circuit after finding that the Board had erred was to remand the matter back to the FDIC for further consideration of petitioner’s case.

The Sixth Circuit, for its part, believed that remand was unnecessary because it “would result in yet another agency proceeding that amounts to ‘an idle and useless formality.’” 37 F. 4th, at 335 (quoting NLRB v. Wyman-Gordon Co., 394 U. S. 759, 766, n. 6 (1969) (plurality opinion)). […]

That exception does not apply in this case. The FDIC was not required to reach the result it did; the question whether to sanction petitioner—as well as the severity and type of any sanction that could be imposed—is a discretionary judgment. And that judgment is highly fact specific and contextual, given the number of factors relevant to petitioner’s ultimate culpability. To conclude, then, that any outcome in this case is foreordained is to deny the agency the flexibility in addressing issues in the banking sector as Congress has allowed.

In light of recent and pending Supreme Court decisions, it is an open question just how much “flexibility in addressing issues in the banking sector” the Court believes Congress to have allowed, but in any case that is all just context for what I thought was an interesting point of contention in the case below, and not one on which the Supreme Court opined either way earlier this week.

Safety and Soundness

To seek removal under Section 8(e) of the FDI Act, the FDIC must first determine that an institution-affiliated party either (i) violated a statute, regulation, cease-and-desist order, or other similar requirement, (ii) engaged or participated in an “unsafe or unsound practice” or (iii) breached a fiduciary duty.

Majority Opinion Approach

Even though the Sixth Circuit majority ultimately held that the FDIC’s determination that Calcutt engaged in an unsafe or unsound practice was supported by substantial evidence, the Sixth Circuit took issue with how the FDIC got there. As relevant here, the Sixth Circuit majority suggested that the FDIC’s approach to evaluating whether a practice is unsafe or unsound was not in keeping with that of several federal appellate courts and was otherwise “not convincing.”

The FDI Act does not define an “unsafe or unsound practice,” and the term is interpreted flexibly. See Seidman v. Off. of Thrift Supervision (Matter of Seidman), 37 F.3d 911, 926–27 (3d Cir. 1994). However, courts have generally treated the phrase as referring to two components: “(1) an imprudent act (2) that places an abnormal risk of financial loss or damage on a banking institution.” Id. at 932; see also Michael v. FDIC, 687 F.3d 337, 352 (7th Cir. 2012) (same); Landry, 204 F.3d at 1138 (identifying imprudent-act and abnormal-financial-risk components).

Calcutt emphasizes the financial-risk component and argues that the Bedrock Transaction did not pose an abnormal financial risk to Northwestern Bank. Along with amicus American Association of Bank Directors, he characterizes the Bedrock Transaction as a good-faith attempt to shore up one of the Bank’s largest lending relationships during the tumult of the Great Recession by releasing collateral and extending a loan that amounted to only a fraction of the Nielson Entities’ total debt. And even if the $760,000 loan and $600,000 in collateral were ultimately not collected, he says, that loss would have been insignificant, considering that the Bank’s Tier 1 capital totaled more than $70 million.

The FDIC responds that the statute does not require a finding of a threat to bank stability in order to find “unsafe or unsound” practice, and that “[c]ourts have affirmed prohibition orders based on unsafe and unsound practices with a much more limited effect.” Br. of Respondent 46. That reading contradicts the analyses of our sister circuits in Seidman, Michael, and Landry, and the decisions that the agency cites in support of its interpretation are not convincing. Ulrich v. U.S. Department of Treasury is a Ninth Circuit memorandum in which the court concluded that a loan “fraught” with financial risk, not just a limited effect, was an unsafe or unsound practice. 129 F. App’x 386, 390 (9th Cir. 2005). Other decisions that the FDIC cites—Gully v. National Credit Union Administration Board, 341 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2003), First State Bank of Wayne County v. FDIC, 770 F.2d 81 (6th Cir. 1985), and Jameson v. FDIC, 931 F.2d 290 (5th Cir. 1991)—did not engage with the question of whether financial risk to the institution was necessary to demonstrate an unsafe or unsound practice. Still other cited decisions linked a finding of unsafe or unsound practices to abnormal financial risks, again controverting the FDIC. See Gulf Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass’n of Jefferson Parish v. Fed. Home Loan Bank Bd., 651 F.2d 259, 264 (5th Cir. 1981); Matter of ***, FDIC-83-252b&c, FDIC-84-49b, FDIC-84-50e (Consolidated Action), 1985 WL 303871, at *9 (FDIC Aug. 19, 1985).

Nonetheless, the Sixth Circuit majority determined that the FDIC’s erroneous application of this portion of the law did not matter here, saying:

Whether or not we interpret the statute to require a finding of abnormal financial risk, however, the FDIC’s finding that Calcutt committed an “unsafe or unsound practice” is supported by substantial evidence…

The Dissent

Judge Murphy in dissent also concluded that the FDIC got the law wrong on what it means to have engaged in an “unsafe or unsound” practice, but for different reasons than the majority.

First, Judge Murphy expressed concern that, without a definition in the statute, courts have adopted an understanding of “unsafe or unsound” that is based on legislative history and that uses an approach “no Justice on the Supreme Court would endorse today.”

Regulators have long defined the key phrase—“unsafe or unsound practice”—using a two-part test that courts have generally accepted. See First Nat’l Bank of Eden v. Dep’t of Treasury, 568 F.2d 610, 611 n.2 (8th Cir. 1978). Under this test, an act qualifies as an unsafe or unsound practice if it conflicts with “generally accepted standards of prudent operation” and creates an “abnormal risk of loss or harm” to the bank. App. 18 (quoting Michael v. FDIC, 687 F.3d 337, 352 (7th Cir. 2012)).

This test was not intuitive to me from a review of the text, so I looked into its origins. One court transparently identified its source: “Because the statute itself does not define an unsafe or unsound practice, courts have sought help in the legislative history.” In re Seidman, 37 F.3d 911, 926 (3d Cir. 1994). The Fifth Circuit started down this path. See Gulf Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass’n v. Fed. Home Loan Bank Bd., 651 F.2d 259, 263–65 (5th Cir. 1981). Rather than seek out the ordinary meaning of “unsafe or unsound practice,” it jumped to a “lively” debate in the congressional record. Id. at 263. During this debate, the court noted, a few legislators had treated as “authoritative” a definition proposed by an agency chairman. Id. at 264. Under the chairman’s view, the phrase covered “any action” that “is contrary to generally accepted standards of prudent operation, the possible consequences of which, if continued, would be abnormal risk or loss or damage to an institution, its shareholders, or the agencies administering the insurance funds.” Id. (citation omitted). The court accepted his view as law. Id. at 264–65.

This straight-from-the-legislative-history test has spread widely since. The few courts with reasoned analysis regurgitate the same bit of legislative history. Seidman, 37 F.3d at 926. Most others, though, simply cite other precedent for this test without considering its origins. See Frontier State Bank v. FDIC, 702 F.3d 588, 604 (10th Cir. 2012); Michael, 687 F.3d at 352; Landry v. FDIC, 204 F.3d 1125, 1138 (D.C. Cir. 2000); Simpson, 29 F.3d at 1425; Doolittle v. Nat’l Credit Union Ass’n, 992 F.2d 1531, 1538 (11th Cir. 1993); Nw. Nat’l Bank v. Dep’t of Treasury, 917 F.2d 1111, 1115 (8th Cir. 1990).

I am troubled by this approach. The test springs from a mode of interpretation that no Justice on the Supreme Court would endorse today. […]

Judge Murphy then acknowledged that in order to address concerns about “open-ended supervision” that could result from adopting a definition of unsafe and unsound practices that is not grounded in the text of the statute, courts have read a limitation into the law, requiring that “an action pose a risk of extreme harm—one that threatens the bank’s ‘financial stability’ . . . or ‘integrity.’”

But to Judge Murphy this does not solve the problem because this limitation, too, seems to him to be basically just made up.

All of this said, courts that apply a broad legislative-history test have recognized that their reading could lead to “open-ended supervision.” Gulf Fed., 651 F.2d at 265. So they compensate by adding a limiting principle that I do not necessarily see in the text either. They have read the phrase “unsafe or unsound practice” to require that an action pose a risk of extreme harm—one that threatens the bank’s “financial stability,” Seidman, 37 F.3d at 928, or “integrity,” Johnson, 81 F.3d at 204 (quoting Gulf Fed., 651 F.2d at 267). An “unsafe” practice (one that exposes the bank to “danger or risk”) may well require a risk of some harm. 2 Oxford Universal Dictionary 2312 (3d ed. 1968). But the statute also covers an “unsound” practice in the disjunctive (a practice that is “not based on proven practice, established procedure, or practical knowledge”). Webster’s New International Dictionary 2511 (3d ed. 1966). Perhaps the entire phrase “unsafe or unsound” may be one of those “doublets” that Congress uses to convey a single idea (like “aid and abet” or “cease and desist”). Doe v. Boland, 698 F.3d 877, 881 (6th Cir. 2012) (citing Freeman v. Quicken Loans, Inc., 566 U.S. 624, 635–36 (2012)). Even still, I would not think that this text requires the risk of financial collapse. A loan officer at a massive bank who has followed a consistent pattern of making bad loans may have engaged in an “unsafe or unsound practice” even if the banker’s portfolio cannot threaten the bank’s existence.

Ultimately, though, Judge Murphy would not have decided this issue, instead concluding that the FDIC was wrong for a different reason.

Be that as it may, I would save the required financial-risk level for another appeal. When sanctioning Calcutt here, the FDIC did not apply my reading that the statute requires unsafe or unsound banking practices. I would remand for it to do so in the first instance. Most notably, the FDIC nowhere indicated that it must identify a banking “practice” as I read the phrase—i.e., a “habitual or customary action[.]” American Heritage, supra, at 1028. To the contrary, as Calcutt notes, the vast majority of its findings relied on a single loan—the Bedrock Transaction. It concluded, among other things, that Calcutt violated the Bank’s lending policies and engaged in imprudent lending by approving that transaction. App. 19–21. It is not clear that Calcutt’s actions with respect to this loan can rise to the level of an unsafe or unsound “practice.”

***

Given the muddled path the case took to get to this point, I am not sure what effect, if any, the arguments of either the panel majority opinion or Judge Murphy’s dissent will have on the FDIC’s approach to the “unsafe and unsound” analysis on remand. (Assuming that question is addressed at all.) But whatever the FDIC decides with respect to Harry Calcutt’s future career in banking,11 it may not be the end of the story, and the case could one day wind up back with the Sixth Circuit or even again in the Supreme Court.12

Thanks for reading! Thoughts, challenges and criticisms are always welcome at bankregblog@gmail.com.

Not discussed in this post, but the proposed bill also includes requirements for the federal banking regulators and the NCUA, among other things, to produce semi-annual reports about their supervisory activities (including confidentially providing to the Chair and Ranking Member information about institutions with unsatisfactory ratings or subject to enforcement action) and to testify periodically before Congress. These provisions may have more cross-party buy-in.

Obvious disclaimer: the sample size here is only three (counting Governor Tarullo’s de facto role).

Ironically, the one Vice Chair for Supervision nominee to date who has failed to achieve Senate confirmation would arguably be the one who comes closest to meeting the narrow reading of this new proposed requirement, having previously served on the Federal Reserve Board and as a state bank supervisor.

I am ignoring for now the possibility of a later court challenge from a financial institution to a Federal Reserve Board supervisory action on the ground that the Vice Chair for Supervision who directed it was statutorily unqualified for the role, which I guess is a theoretical possibility but seems like an uphill fight.

Cf. this speech by Governor Bowman, in which she suggested that an independent review “would help to eliminate the doubts that may naturally accompany any self-assessment prepared and reviewed by a single member of the Board of Governors.”

I suppose one counterargument is that in theory due to early vacancies or other circumstances you could wind up with a situation where the Vice Chair for Supervision was nominated by a President of one party while a majority of the Board has been appointed by a President of another party, and thus the Board majority’s efforts to exercise “oversight and control” over the Vice Chair for Supervision’s activities becomes a point of contention. I am not sure this is massively different from the situations that could arise under current law, however.

As of the time of this writing the witnesses’ prepared testimony has not been posted, although I would guess that the prepared testimony of Mr. Clements would not differ much from what he has previously said before Congress on this issue.

This quote is from the Sixth Circuit’s decision from last year. The block quote that follows is from Monday’s Supreme Court decision.

From the Sixth Circuit’s decision:

[Calcutt’s] first hearing in these proceedings occurred before an FDIC administrative law judge (“ALJ”) in 2015. Before the ALJ released his recommended decision, the Supreme Court decided Lucia v. SEC, 138 S. Ct. 2044 (2018), which invalidated the appointments of similar ALJs in the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). The FDIC Board of Directors then appointed its ALJs anew, and in 2019 a different FDIC ALJ held another hearing in Calcutt’s matter and ultimately recommended penalties.

A few outside groups, including the American Association of Bank Directors, also filed briefs in support of various arguments made by Mr. Calcutt. You can read those briefs here.

Mr. Calcutt’s cert petition noted that he “is now Chairman of State Savings Bank, a profitable and well-capitalized community bank, and its holding company, CS Bancorp.”

In case looking for an arguably more authoritative opinion on this than an internet blog about bank regulation, see this take from a law professor:

1) There are a bunch of interesting issues buried in this case, so I would not be surprised at all were we to see it reach SCOTUS again after remand to the agency.