Operational Risk Capital

More context on one aspect of the forthcoming changes to the U.S. capital rules

The Wall Street Journal reported last Monday on the forthcoming Basel III endgame rules from the U.S. federal banking regulators, saying that the end result of the new rules for certain larger banks could be a 20% increase in capital requirements. One of several points of contention relates to a new methodology for calculating risk weighted assets for operational risk.

[Critics in the banking industry] also say the proposal could punish banks for relatively benign services that revolve around fee income. The new rules are expected to treat fee-based activities as an operational risk, a category that includes the potential to lose money from flawed internal processes, people and systems or from external threats such as cyberattacks.

To try to provide additional context to what is going on, this post looks at:

how Basel operational risk capital requirements have evolved;

the approach the U.S. regulators have previously chosen to take in adopting explicit operational risk capital requirements (for some but not all banks) in the United States;

the new Basel standard for calculating RWAs for operational risk and the relevance of fee-based activities to this calculation;

why banks argue that fee-based activities are subject to disproportionate treatment under the new Basel standard; and

choices the U.S. banking regulators will have to make when adopting something like the new Basel operational risk standard, should they choose to do so.

Basel I and Basel II

The original Basel Capital Accord reached in 1988 did not include an explicit capital charge for operational risk. Various changes were made over the next few years, but in June 1999, the Basel Committee released a consultation on a more comprehensive “new capital adequacy framework to replace the 1988 Accord.” This new framework would be become known as Basel II.

In the 1999 consultation, the Basel Committee explained:

The existing Accord specifies explicit capital charges only for credit and market risks (in the trading book). Other risks, including interest rate risk in the banking book and operational risk, are also an important feature of banking. The Committee therefore […] is proposing to develop capital charges for other risks, principally operational risk.

The consultation acknowledged that “in the absence of industry standard practice, operational risk will be difficult to incorporate into the risk-based capital framework in a truly risk-sensitive manner.” The Committee then floated various potential approaches, including “basing a capital charge on a measure of business activities such as revenues, costs, total assets, or, at a later stage, internal measurement systems, or creating differentiated charges for businesses with high operational risk based on measures commonly used to value those business lines.”

Regulators were skeptical that, at least in 1999, internal models were up to the job, but asked for input from banks on this point.

The Committee is also aware that there are other possible methods of allocating regulatory capital for operational risk. One would be to permit banking organisations to use models. For this option, particular regard would need to be paid to the robustness of the model, the quality of the data, stress-testing, the extent to which it responds to changes in exogenous variables, and the areas of operational risk not covered by the model. (Depending on the quality of the model, supervisors could still apply a multiplier or other adjustment factor to the model output). The Committee perceives that, at the moment, very few, if any, banks have a model that meets these criteria, and that, therefore, such models could only be used at a later stage. However, the Committee invites submissions from banks that perceive their models to be functioning well.

By the time that the international Basel II standards were finalized in June 2004, the Basel Committee had a somewhat more favorable view of internal models. The Committee decided to include in the new framework three methods for calculating RWAs for operational risk existing along “a continuum of increasing sophistication and risk sensitivity”: the Basic Indicator Approach, the Standardised Approach, and the Advanced Measurement Approaches.

As summarized by the U.S. banking regulators:

The first method, called the Basic Indicator Approach, requires banks to hold capital for operational risk equal to 15 percent of annual gross income (averaged over the most recent three years).

The second option, called the Standardized Approach, uses a formula that divides a bank’s activities into eight business lines, calculates the capital charge for each business line as a fixed percentage of gross income (12 percent, 15 percent, or 18 percent depending on the nature of the business, again averaged over the most recent three years), and then sums across business lines.

The third option, called the Advanced Measurement Approaches (AMA), uses a bank’s internal operational risk measurement system to determine the capital requirement.

The Basel Committee explained that “[b]anks are encouraged to move along the spectrum of available approaches as they develop more sophisticated operational risk measurement systems and practices.” The Committee also stated that “[i]nternationally active banks and banks with significant operational risk exposures (for example, specialized processing banks) are expected to use an approach that is more sophisticated than the Basic Indicator Approach.”

Basel II in the United States

As relevant to operational risk capital, the U.S. federal banking regulators made two key decisions in the course of adopting final rules in 2007 to implement portions of the Basel II agreement.1

First, the regulators identified a group of “core banks” (now more commonly called advanced approaches banks), which were required to use the most advanced methods to determine RWAs for credit risk and RWAs for operational risk. The threshold for application of these rules was set at either $250 billion in total consolidated assets or $10 billion in consolidated total on-balance sheet foreign exposure. Banks below this threshold were allowed, but not required, to adopt the new approaches. $250 billion/$10 billion would remain the advanced approaches threshold until the tailoring rules were adopted in 2019.

Second, the regulators determined that, although the Basel II agreement featured three options for calculating RWAs for operational risk, it was best to require the banks subject to the new rules in the U.S. (that is, only the largest and most internationally active banks) to “comply with the most advanced approaches.” In the case of operational risk capital, this meant the Advanced Measurement Approaches.

As implemented in the United States, the AMA requires banks to maintain appropriate operational risk management practices; operational risk data and assessment systems; and operational risk quantification systems, in each case subject to parameters set out in the rules. For instance, a bank’s operational risk data and assessment systems must take into account internal operational loss event data, external operational loss event data, scenario analysis, and business environment/internal control factors.

Once a bank’s practices, systems and controls have met these requirements, the bank calculates its expected operational loss (EOL) and its unexpected operational loss (UOL). For these purposes:

Operational loss means a loss resulting from an operational loss event.2

EOL is the expected value of the distribution of potential aggregate operational losses, as generated by an operational risk quantification system using a one-year horizon.

UOL is the difference between a bank’s operational risk exposure and the bank’s EOL.

Operational risk exposure means the 99.9th percentile of the distribution of potential aggregate operational losses, as generated by a bank’s operational risk quantification system over a one-year horizon (and not incorporating eligible operational risk offsets3 or qualifying operational risk mitigants4).

These calculations then serve as inputs into a bank’s dollar risk-based capital requirement for operational risk as follows:

If a bank does not have or does not qualify to use operational risk mitigants, the bank’s dollar capital requirement for operational risk is its operational risk exposure minus its eligible operational risk offsets (if any).

If a bank has operational risk mitigants, the bank’s dollar capital requirement for operational risk is the greater of:

Operational risk exposure (adjusted for mitigants) minus eligible operational risk offsets (if any); or

0.8 multiplied by the difference between (i) operational risk exposure and (ii) eligible operational risk offsets (if any).

This number is then multiplied by 12.5 to arrive at an RWA amount.

The U.S. banking regulators explicitly acknowledged that, given the AMA’s reliance on internal models, banks would necessarily use different inputs and methodologies in quantifying operational risk, and thus there was likely to be at least some variation in results. The agencies were comfortable with this “inherent flexibility” of the AMA, subject to certain safeguards.

The agencies recognize that banks will have different inputs and methodologies for estimating their operational risk exposure given the inherent flexibility of the AMA. It follows that the weights assigned in combining the four required elements of a bank’s operational risk data and assessment system (internal operational loss event data, external operational loss event data, scenario analysis, and assessments of the bank’s business environment and internal control factors) will also vary across banks. […] As such, the agencies are not prescribing specific requirements around the weighting of each element, nor are they placing any specific limitations on the use of the elements. In view of this flexibility, however, under the final rule a bank’s operational risk quantification systems must include a credible, transparent, systematic, and verifiable approach for weighting the use of the four elements.

Basel III

The Basel Committee made significant changes to other aspects of the Basel framework in the years immediately after the 2008 financial crisis, but for the moment left the approach to operational risk capital calculation alone.

Similarly, the U.S. implementation of the Basel III rules left the U.S. approach to operational risk capital calculation adopted in 2007 unchanged. This means that under the current U.S. capital rules (i) only a handful of banks are required to calculate RWAs for operational risk5 and (ii) to the extent that a bank is required to do so, it must use the AMA.6

Basel Endgame/Basel IV

The Basel Committee did not believe its work to update the Basel capital standards was fully completed with the changes made immediately after the 2008 financial crisis. This is why the regulators’ preferred nomenclature for the yet-to-be-implemented changes is the Basel III finalization or the Basel III endgame, rather than Basel IV.7

But whatever you call it, as early as 2014 the Basel Committee was saying that there were more improvements they wanted to make to the overall Basel framework, this time including changes to operational risk capital. In its 2014 consultation, the Basel Committee indicated it was most concerned about the simple approaches - i.e., the approaches other than the AMA.

In the wake of the financial crisis, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has been reviewing the adequacy of the capital framework. The aim is not only to address the weaknesses that were revealed during the crisis, but also to reflect the experience gained with implementation of the operational risk framework since 2004. At that time, the Committee made clear that it intended to revisit the framework when more data became available. Despite an increase in the number and severity of operational risk events during and after the financial crisis, capital requirements for operational risk have remained stable or even fallen for the standardised approaches. This indicates that the existing set of simple approaches for operational risk … do not correctly estimate the operational risk capital requirements of a wide spectrum of banks.

These weaknesses in the simpler approaches were especially apparent for “large and complex banks” and, furthermore, these “undercalibrated” simpler approaches had downstream effects on the AMA, as the AMA was “often benchmarked against” the simpler approaches.

The Committee’s next consultation, this one in March 2016, was more direct in its criticism of the AMA. The Basel regulators noted that when the AMA was adopted in 2006, its principles-based framework was supposed to enable a narrowing in practices over time, ultimately leading “to the emergence of a best practice.” This development, however, “failed to materialise.” Instead, “[t]he inherent complexity of the AMA and the lack of comparability arising from a wide range of internal modelling practices … exacerbated variability in risk-weighted asset calculations, and … eroded confidence in risk-weighted capital ratios.”8

So the Basel Committee concluded that the AMA should be ditched and that there should only be one approach to calculating RWAs for operational risk — a newly created standardized measurement approach (SMA).

The SMA directs banks to determine their operational risk capital requirement by calculating a Business Indicator Component (BIC) and then multiplying the BIC by an internal loss multiplier (ILM).

The Business Indicator Component

There is some basic math involved but the general idea is that rather than using internal models, a bank’s RWAs for operational risk will now be based on a less subjective (sort of?) input: a bank’s financial statements.

More specifically, a bank first calculates its Business Indicator by adding together (1) an interest, leases and dividends component, (2) a services component and (3) a financial component, calculated as below.

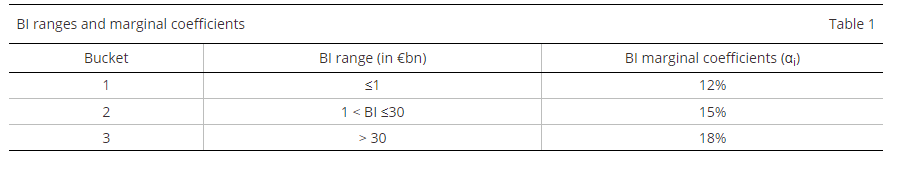

That gives a bank its Business Indicator. Then, to determine its Business Indicator Component, the bank multiplies its Business Indicator by marginal coefficients that increase as the Business Indicator amount increases.

So returning to the WSJ article quoted at the outset of this post, when it says that the new rules are expected to treat fee-based activities as an operational risk, what it means is that fee income and fee expenses are used in calculating the Business Indicator as set out above. And because of the way that the three components of the BI are calculated, banks believe the services component of the BI calculation becomes a disproportionate and inappropriate driver of the overall operational risk capital requirement.

The services component … drives these outsized operational risk charges because the BI formula generates higher RWAs from noninterest income than from interest income. Specifically, the operational risk capital requirement tied to interest income offsets interest income with interest expense and is no higher than 2.25 percent of interest-earning assets. By contrast, the operational risk capital charge tied to noninterest income does not offset revenues with expenses and it is uncapped. The decoupling between the interest and services components penalizes banks with a business mix tilted toward noninterest income in the absence of any evidence of higher operational risk. In addition, the differences in capital requirements across the interest and services components misaligns the risk of banking products that generate both interest income and noninterest revenue, such as credit cards.

The Internal Loss Multiplier

In theory, the BIC is not on its own the determinant of RWAs for operational risk. As noted above, under the Basel SMA the BIC is meant to be multiplied by an internal loss multiplier based on a bank’s annual operational risk losses over the previous ten years.

The formula is below, but the general idea is that if a bank has a history of operational risk losses relative to its BIC, its ILM will be greater than 1 and the bank’s capital requirement will increase. Conversely, a bank with a relatively low amount of historical operational risk losses in comparison to its BIC could have an ILM less than one, and thus have a lower capital requirement.

The Basel framework, however, gives regulators the option to disregard bank-specific individual loss histories and instead set the ILM at 1 for all banks in their jurisdiction. If so, this has the effect of making the BIC the sole factor in determining a bank’s RWAs for operational risk under the SMA. This is the approach that the EU9 and the UK10 have proposed to take.

Decisions for the U.S. Banking Regulators

I suppose that, given its announced attention to conduct a holistic review of capital standards, it is possible the Federal Reserve Board concludes that existing capital levels are just fine and the new Basel standard need not be adopted here. But living in the real world, it seems more likely that the holistic review is going to produce something at least within touching distance of the finalized Basel standards.

If that’s right, I think the following are the big picture issues for decision when it comes to operational risk.

First, as with other aspects of the revised rules, the U.S. regulators need to determine the banks to which the new SMA for operational risk will apply. As a general matter, the conventional wisdom is that the definition of advanced approaches bank is going to be broadened, not only to go back to the pre-2019 definition (which would scope in very large regional banks) but also perhaps to scope in all firms with $100 billion or more in total assets, at least for purposes of certain requirements. If this is the approach the agencies take as a general matter, will the agencies also take that approach for the SMA? Or, regardless of any more general broadening of the advanced approaches group of banks, will the SMA only apply to a smaller subset of firms, similar to how the AMA applies today?

Second, U.S. regulators will need to evaluate whether they are comfortable with the SMA’s formulation of the Business Indicator Component, including but not limited to its treatment of fee-based activities. The Bank Policy Institute post I linked to above recommended in May 2022 that the regulators modify the BIC calculation “by capping the BI’s services component at 2.25 percent of a banking institution’s total assets (less reserve balances, Treasuries, and Agency MBS to mitigate procyclicality).”11 It is not clear whether this or other modifications to the BIC calculation are actively under consideration by the U.S. banking regulators.

Third, U.S. regulators must decide whether to have banks determine a bank-specific ILM based on the bank’s history of losses, or whether the ILM should instead be set at 1 for all banks subject to the SMA. The industry take, for what it’s worth, is that setting the ILM at 1 is the better approach because “large operational risk losses are rare, given that they represent unexpected and unforeseen circumstances, and are not necessarily predictive of future losses. Additionally, as business models change over time, the informational value of past losses diminishes.”

Finally, although not directly related to the SMA implementation questions above, the Federal Reserve Board likely will also be asked to decide whether any changes are necessary to its estimates of operational risk losses in its annual supervisory stress test. For purposes of projecting a bank’s operational risk losses in the supervisory stress scenario, the Federal Reserve Board uses a methodology that has as its key components “the size of the firm measured by total assets and the firm’s historical operational-risk losses by operational-risk event.”

The result is that, holding all else equal, the larger a bank is by total assets, the larger its projected operational risk losses under the stress test. Large banks, understandably, would prefer a different result. For example, last year Bank of America requested reconsideration of its stress capital buffer determination, arguing that, as relevant here, “the increase in its noninterest expense projections is due to an overly simplistic dependence of the Federal Reserve’s models for expenses and operational losses—which are included in noninterest expenses—on firms’ total assets.”

The Federal Reserve Board, as it has done for every other appeal so far under the stress capital buffer regime, denied Bank of America’s request for consideration, saying that the methodology with which Bank of America took issue was “consistent with the Supervisory Stress Test Methodology Disclosure.”12

The Federal Reserve did say in its conclusion to the letter that “the Board has directed Federal Reserve staff to explore possible refinements to the models used to produce the disclosed noninterest expense projections to better reflect the composition of firms’ total assets.” Whether this staff exploration or other investigations the staff have been directed to conduct13 will result in any changes to the Board’s stress testing methodologies remains to be seen.

Thanks for reading! Are there other big picture questions about operational risk capital that I have missed? Thoughts, challenges or criticisms on this point or any others are always welcome at bankregblog@gmail.com.

The final rule discussed here is the final rule adopting the Basel II credit risk RWA and operational risk RWA changes. Changes to market risk RWAs were addressed in a separate series of rulemakings.

The capital rules describe operational loss events as including internal fraud; external fraud; employment practices and workplace safety; clients, products and business practices; damages to physical assets; business disruption and system failures; and execution, delivery and process management.

Operational risk offsets are amounts generated by internal business practices to absorb highly predictable and reasonably stable operational losses, including reserves calculated consistent with GAAP, provided such amounts are available to cover expected operational losses with a high degree of certainty over a one-year horizon.

Operational risk mitigants are insurance (provided it meets certain conditions) and other mitigants (if any) for which the federal banking regulators have given prior written approval based on an assessment of whether the operational risk mitigant covers potential operational losses in a manner equivalent to holding total capital.

Currently the only advanced approaches U.S. banks are the eight U.S. G-SIBs and Northern Trust. As previously discussed, this is a result of a change made by the tailoring rules in 2019 which worked to the benefit of large U.S. regionals that otherwise would have been covered by the rules because they had either $250 billion or more in total assets or on-balance sheet foreign exposure of at least $10 billion.

See pages 37-38 here for an example of a how a BHC subject to the AMA reports its operational risk calculations to the Federal Reserve Board, but as you can see other than the top-line number everything is confidential.

This preference has featured humorously (I think) in various speeches from regulators. For instance:

William Coen, then-Secretary General of the Basel Committee in 2018: “Rest assured: I don't expect Basel IV to happen anytime soon (though some in the industry may think that it already has happened)!”

“Thank you for not calling it Basel four,” the Federal Reserve Board’s General Counsel said at a 2019 conference.

“The finalisation of Basel III – and not of Basel IV, definitely not – brings to an end a decade of regulatory efforts…” said the governor of the Bank of France in 2023.

This view was not limited to the Basel Committee. As BPI wrote in May 2022:

Although the Basel Committee defined the AMA operational-risk exposure as the 99.9th percentile of the distribution of aggregate operational-risk losses over a one-year horizon, making such an estimation with any degree of accuracy is impossible, so taking such estimates seriously is silly. In practice, banks could use various models including scenario analysis or extreme value theory to quantify operational risk. However, the lack of concrete guidance led to huge variability in operational-risk charges across jurisdictions, especially since not all jurisdictions were as permissive in terms of allowing banks to use scenario analysis to lower their AMA models’ outputs.

For whatever it’s worth, the European Central Bank was not happy with the European Commission’s approach in this regard:

While the ECB acknowledges that the Basel III framework offers the possibility to disregard historical losses for the calculation of capital requirements for operational risks, it regrets that the Commission did not opt for a recognition of these losses. The ECB considers that taking into account the loss history of an institution would entail more risk sensitivity and loss coverage of capital requirements, addressing the divergence of risk profiles of institutions in highly sensitive issues such as conduct risk, money laundering or cyber incidents, and would provide greater incentives for institutions to improve their operational risk management.

See paragraphs 8.23-8.26 here for the PRA’s reasoning.

BPI further observes:

For some lines of business, it would also be logical to offset fee income with fee expense because the product generating the two flows is the same (e.g., credit card fees are aligned with credit card member rewards). However, for other firms, the fee income source is mainly from investment banking and fiduciary fees while the major source of expenses comes from brokerage and clearing activities. In this latter case, offsetting fee income with fee expenses is less straightforward because there is less of a comparable relationship between services offered and services used. That said, this is a topic that deserves further analysis beyond the one done in this note.

As previously discussed, the standard of review the Board has used for stress capital buffer appeals is (1) whether there have been any math errors and (2) whether the Board’s models are operating as designed. Because many banks’ complaints at their core are not about whether the Board’s models are operating as designed but rather about whether the models are appropriately designed in the first place, no bank has yet succeeded in a request for reconsideration.

For instance:

The Board’s letter rejecting HSBC’s 2021 request for reconsideration “directed Federal Reserve staff to investigate and address, as appropriate, the risk sensitivity of the commercial real estate model to see if any future improvements can be made.”

The Board’s letter rejecting BMO’s 2020 request for reconsideration “directed Federal Reserve staff to explore potential improvements through the use of more recent data for purposes of PPNR model development and estimation.”

The Board’s letter rejecting Citizens Financial Group’s 2020 request for reconsideration “directed Federal Reserve staff to investigate and address, as appropriate, the treatment of loss-sharing agreements in certain retail models to see if any future improvements can be made.”

The Board’s letter rejecting Goldman Sachs’s 2020 request for reconsideration “directed Federal Reserve staff to investigate and address, as appropriate, the incorporation of portfolio credit quality in modeling losses on loans that use FVO accounting to see if any future improvements can be made. In addition, the Board has directed Federal Reserve staff to explore potential improvements with regard to the granularity of the approach to estimating trading revenues for firms subject to the GMS, estimating expenses based on revenues instead of macroeconomic variables, and using flexible pricing options in projecting losses.”

The Board’s letter rejecting Regions’s 2020 request for reconsideration “directed Federal Reserve staff to investigate and address, as appropriate, the treatment of interest-rate hedges in projecting PPNR to see if any future improvements can be made.”