Four Arguments About the Basel Endgame, Long-Term Debt or GSIB Surcharge Proposals

Operational risk, a potential FR Y-15 mistake, Section 165(d) and the EGRRCPA, and LTD minimum requirements

Last Tuesday was the deadline for comments on three proposals issued in 2023 by the U.S. federal banking regulators: (1) proposed “Basel Endgame” changes to the capital rules applicable to banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets, (2) a proposal to apply a long-term debt requirement to banking organizations (other than U.S. GSIBs) with $100 billion or more in total assets and (3) proposed revisions to the U.S. GSIB surcharge.1

The broad outlines of the comments have by this point received a fair amount of discussion — see for instance recaps here from the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Capitol Account, Law360 and the American Banker2 — so I thought in this post I would focus on four technical or legal arguments about the proposals.3

1. On Operational Risk Capital Charge, Some Differences Between Banks on Their Preferred Changes

The Basel Endgame proposal’s operational risk capital charge was a focus of many commenters, as noted in some of the recaps linked above. What has been less covered to this point, though, are the specifics of the changes banks would like to see, including differences of opinion that have emerged on certain points.

The operational risk capital requirement would be calculated by multiplying a Business Indicator Component (BIC) by an Internal Loss Multiplier (ILM).4 My discussion here thus focuses on the BIC and the ILM, although as discussed briefly below several commenters also raise other issues with the overall approach to operational risk in the proposal, including its interaction with other rules.

The Business Indicator Component, As Proposed

Business Indicator

In broad terms, the Business Indicator is intended to account for a bank’s (1) lending and investment activities (the “interest, lease and dividend component”), (2) fee and commission-based activities (the “services component”), and (3) trading activities (the “financial component”).

Interest, Lease, and Dividend Component = min ( Avg3y ( Abs (total interest income − total interest expense)), 0.0225 * Avg3y ( interest earning assets)) + Avg3y (dividend income)

Services component = max (Avg3y (fee and commission income), Avg3y ( fee and commission expense) ) + max (Avg3y(other operating income),Avg3y ( other operating expense))

Financial Component = Avg3y (Abs (trading revenue)) + Avg3y (Abs (net profit or loss on assets and liabilities not held for trading))

As relevant to the comment letters discussed below, there are two key things to note about the above formulas. First, the services component is calculated based on gross rather than net amounts. In other words, unlike the interest, lease and dividend component and the financial component, revenues are not offset with expenses. Second, the services component, unlike the interest, lease and dividend component, is uncapped.

These features of the services component have led banks to argue that the operational risk capital charge would disproportionately penalize fee-based activities.5

BIC Coefficients

To arrive at the BIC, the Business Indicator is multiplied by what the Basel Committee describes as “a set of regulatory determined marginal coefficients,” such that the BIC increases with the size of the Business Indicator.

In the proposal, the agencies explained that these coefficients are intended to “reflect exposure to operational risk generally increasing more than proportionally with a banking organization's overall business volume, in part due to the increased complexity of large banking organizations.”

The Business Indicator Component: Banks’ Proposed Changes

Business Indicator

The comment letters present an array of possible changes to the Business Indicator. The three that come up most often (in various forms) are:

Permitting commission and fee income to be offset with commission and fee expense.

Treating different types of commission and fee income differently depending on the business line that generates the income and the historical losses associated with it.

Adopting some sort of cap, for example on the contribution that fee income could make to the services component, or on the contribution the services component could make to the Business Indicator as a whole.

See the BPI/ABA letter for an illustrative discussion of these options, which the trade groups say need not be exclusive, and could be adopted in combination with each other.

Other letters endorsing one or more of these options (again, not necessarily always in the same form6) include letters from Barclays, BNY Mellon, the Institute of International Bankers, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Northern Trust, State Street, Synchrony, and Wells Fargo.

One other letter worth mentioning comes from American Express, which says that under the proposal it “would see a very significant overall increase in capital requirements – expected to be the highest impact among domestic non-GSIB banks.” The American Express letter endorses, as fallback options, netting and cap ideas similar to those in the letters above.

American Express’s lead recommendation, however, is a little different. They argue that fees generated by, and expenses attributable to, charge and credits cards should be accounted for in the interest, lease and dividend component, rather than the services component.

Absent a correction, the result of the Proposed Rules would be one that defies logic and lacks historical support, and that the Agencies presumably did not intend: our set of longstanding, non-exotic, well-understood lending and payments activities would incur an increased operational risk capital charge substantially higher than any comparable business at another banking organization. To avoid this inappropriate and unique misalignment of capital to risk, we recommend the Agencies include the revenue derived from all types of card products, including the associated discount revenue, along with the expenses attributable to these activities, in the Interest Component to reflect the direct relationship between these revenues and expenses and the associated payments and lending activities, and to ensure that fee revenue and expenses associated with card products are not treated punitively or as disproportionately risky.

BIC Coefficients

While comparatively less of a focus, a few letters also make recommendations on the BIC coefficients. For example, BPI and ABA “suggest a reduction in the coefficients of the BIC to further decrease the RWAs for operational risk and an adjustment to the business indicator ranges to account for economic growth and inflation relative to 2017,” while JPMorgan argues that the BIC coefficient should be set at “a fixed 12% to reduce the excessive overall calibration of operational risk RWA and the magnified impact of marginal increases in revenue and expenses for larger firms.”

The Internal Loss Multiplier, As Proposed

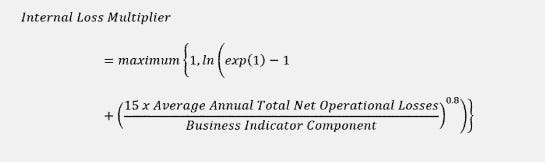

The Internal Loss Multiplier is meant to be based on a bank’s history of operational risk losses and relative to its BIC. As proposed, this works by:

taking the average of a bank’s annual net operational loss events7 over the past ten years,8

multiplying that number by 15,9

dividing the result by the BIC, and

dampening the results to “constrain the volatility of the operational risk capital requirement.”10

In this respect, the U.S. proposal’s approach to the ILM is generally consistent with the Basel standard. There is one additional feature of the U.S. proposal, however, that is different from both the Basel standard and from how other large jurisdictions have approached the ILM.

The Basel standard contemplates that if a bank has a history of elevated losses relative to its BIC the ILM calculation would produce an ILM greater than 1 (and thus, holding all else equal, a higher operational risk capital charge). In contrast, if a bank has a history of lower-than-expected losses relative to its BIC, the ILM calculation could produce an ILM less than 1. This has been termed the floating ILM approach.

The Basel standard also leaves open the possibility for jurisdictions to choose not to adopt the ILM calculation, and instead just set the ILM at 1 for all firms, meaning the operational risk capital charge would be determined solely by the BIC. A few jurisdictions, including the EU and UK, have said that they intend to set the ILM at 1. This has been termed the fixed ILM approach.

In their proposal, the U.S. banking regulators rejected both the floating and the fixed ILM approaches. Instead, the agencies proposed to floor the ILM at 1. In other words, a bank with an elevated history of operational risk losses could still have an ILM above 1, but a bank with minimal historical operational risk losses could not reduce its ILM below 1.

Taking all the above into account, the formula for the ILM in the proposal looked like this.

The Internal Loss Multiplier — Banks Proposed Changes

Fixed vs. Floating ILM

A letter from the Advanced Operational Risk Group of the Risk Management Association, the membership of which consists of large and mid-sized U.S. and foreign banks, acknowledges “a range of perspectives among the AORG membership” on whether the ILM should be fixed at 1 or should be allowed to float.11

Perhaps reflecting that tension, the BPI/ABA letter does not firmly endorse one option over the other:

Unless and until the agencies can provide relevant data and analysis for public consideration, the agencies should consider setting the ILM to one. As we discuss in further detail below, however, simply setting the ILM equal to one would not address the broad-based over-calibration of the operational risk capital charge, and additional changes would be required. Another alternative would be to let the ILM float symmetrically and reduce the ILM formula multiplier to address the broad-based over-calibration as we discuss in more detail below.

A few individual letters, however, do stake out more of a firm position.

Letters endorsing a fixed ILM of 1 as their primary recommendation with respect to the ILM include letters from the Bank Crisis Response Working Group of the Risk Management Association, Barclays, the Institute of International Bankers,12 Morgan Stanley, the Securities Lending Council of the Risk Management Association, U.S. Bancorp, Synchrony, and Wells Fargo.

JPMorgan’s letter takes the opposite position, saying that “setting ILM equal to 1 would disproportionately and incongruously benefit banks with higher historical operational losses.” Therefore, JPM believes a floating ILM (combined with other changes discussed above and below) would be the best approach. Other letters endorsing a floating ILM include letters from Northern Trust13 and a group of banking organizations currently in Category IV or approaching Category IV.

The 15x Multiplier

As a few letters point out, given that the ILM is calculated based on a bank’s operational risk losses relative to its BIC, the changes to the BIC that banks recommend as discussed above could, if the ILM calculation is not adjusted, have the effect of increasing the ILM.

Therefore, assuming the ILM isn’t fixed at 1, some of the letters also recommend changes to the 15x multiplier in the ILM calculation. See letters from BPI/ABA, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo.

Other Recommendations

The focus of this section has been on the BIC and the ILM, as I find those arguments most interesting, but to be clear, banks do not necessarily believe that even if all of these changes were adopted the operational risk issue would be fixed. Several of the letters linked above also take issue with what they see as the overlap between the proposed operational risk capital charge and the stress capital buffer framework. Some letters also, before getting to specific recommendations on the BIC and ILM, offer arguments that certain banks or groups of banks should not be subject to the operational risk capital charge in the first place.

2. GSIB Surcharge Proposal: Are the Federal Reserve Board’s Projections of the Effects on Foreign Banking Organizations Just a Big Misunderstanding?

Under current U.S. capital rules, the eight U.S. global systemically important banks are subject to an additional capital requirement known as the GSIB surcharge.14

Last summer, at the same time the Basel Endgame proposal was published, the Federal Reserve Board proposed changes to the U.S. GSIB surcharge framework intended to “improve [its] precision … and better measure systemic risk.” In connection with that proposal, the Board would also amend the FR Y-15 reporting form, which is the form on which firms report the systemic risk indicators used in calculating the GSIB surcharge.

Though the U.S. GSIB surcharge applies only to the U.S. GSIBs, changing the FR Y-15 has the potential to affect more than just those firms. This is because information reported on the FR Y-15 is also used by the Federal Reserve Board to determine the regulatory category applicable to banking organizations under the tailoring rules adopted in 2019. So, changes to how certain systemic risk indicators are calculated could have downstream effects on large banking organizations that are not U.S. GSIBs were it to cause those banking organizations to report risk-based indicators that place them into a different category of regulation.

Would any of the proposed changes to the U.S. GSIB surcharge calculation (and in turn the FR Y-15) have that effect here? It’s actually not clear. In the proposal, the Board indicated that one set of changes would in fact produce that result, but as explained below a trade group suggests that maybe this was just a mistake in how the Board did the math.

Cross-Jurisdictional Activity Changes

The change at issue here relates to how cross-jurisdictional activity is calculated. In the proposal, the Board said that it had determined that the definition of cross-jurisdictional activity should be amended to include derivatives exposures.

Under the current FR Y–15 instructions, neither of these indicators for cross-jurisdictional activity include derivative exposures. Derivatives, however, can give rise to cross-jurisdictional claims and liabilities, present sources of cross-border complexity, and act as channels for transmission of distress in the same manner as other assets and liabilities or even to a greater extent to amplify the effect of a banking organization's failure. (The failure of Lehman Brothers during the 2007–09 financial crisis presents a notable example.) Omission of derivatives from the systemic indicators for cross-jurisdictional activity can materially understate this measure for a banking organization, and also present opportunities for a banking organization to use derivatives to structure its exposures in a manner that reduces the value of its systemic indicators without reducing the risks the indicator is intended to measure.

Accordingly, the proposal would revise the systemic indicators for cross-jurisdictional claims and cross-jurisdictional liabilities to include derivative exposures. As a result of this change, these indicators would provide a more accurate and comprehensive measure of a banking organization's cross-jurisdictional activity and the associated risks intended to be captured.

According to the Board’s impact analysis, this revision to the definition of cross-jurisdictional activity, while not changing the regulatory category of any U.S.-headquartered bank, would have significant effects for a number of non-U.S. banks.

For the combined U.S. operations of most foreign banking organizations that have combined U.S. assets of $100 billion or more, the reported value of cross-jurisdictional activity would increase above $75 billion as a result of the proposal. This change would result in seven foreign banking organizations that are currently subject to Category III or IV standards becoming subject to Category II standards, which include requirements for daily liquidity reporting (rather than monthly or no liquidity reporting); monthly (rather than quarterly) internal liquidity stress testing; and full (rather than reduced) liquidity risk management. […]

For the U.S. intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations, the Board estimates that the increase in the reported value of cross-jurisdictional activity would move two firms that are currently subject to Category III standards to Category II, making them subject to more stringent capital and liquidity requirements.

IIB Comments

The Institute of International Bankers, a trade group for foreign banks doing business in the United States, argues that, if the Board’s projections are correct, this would “signal[] a severe miscalibration of the GSIB Surcharge Proposal and the CJA risk-based indicator.” Later on in the letter, IIB worries that the Board has engaged in “outcome-based targeting of the U.S. operations of international banks.”

More interestingly, though, IIB also writes that maybe the Board’s impact analysis simply reflects a mistake, such that these changes would not have the effects that the Board in the proposal projected them as having.

As IIB explains, the issue is that under the proposed revised FR Y-15 instructions (and consistent with how the FR Y-15 currently works) foreign banks for purposes of calculating cross-jurisdictional activity would exclude inter-affiliate liabilities and certain inter-affiliate claims. Taking literally the proposed revised FR Y-15 reporting form itself, however, would mean that foreign banks would not be allowed to exclude such liabilities.

From the comment letter (which was joined by BPI):

The Federal Reserve released both the proposed revisions to the Form FR Y-15 and the proposed revisions to the Instructions for the Preparation of Form FR Y-15 in August 2023, but the two documents paint a very different picture as to the intended scope of changes to the CJA indicator.

The Proposed FR Y-15 Instructions properly carry over, into the derivative calculations and into the combined U.S./foreign bank form changes, the current treatment afforded to international banks with regard to cross-jurisdictional claims and cross-jurisdictional liabilities with affiliated entities outside the United States and with U.S. branches of affiliated non-U.S. banks. The Proposed FR Y-15 Instructions set forth the calculation for cross-jurisdictional liabilities in a revised Schedule E: “Line Item 7 Total cross-jurisdictional liabilities. For domestic firms, the sum of items 5 and 6. For FBOs, the sum of items 5(a) and 6(a).” Also, for items 5(a) and 6(a), as per the 2019 Final Tiering Rule, the Proposed FR Y-15 Instructions state: “For this item, do not include liabilities to offices of the FBO outside the reporting group.”

However, in contrast to the Instructions, the Proposed FR Y-15 Form indicates in the individual line item revisions for what will become line item 7 of Schedule E, “Total Cross-Jurisdictional Activities”, that the total is the “sum of items 5 and 6”. These changes omit language stating “sum of items 5.a and 6.a for FBOs”, as indicated in the Proposed FR Y-15 Instructions.

IIB and BPI go on to say that, assuming the proposed FR Y-15 instructions are right and the proposed FR Y-15 form is wrong, this is likely the reason the Board’s impact analysis indicated that many foreign banks would be moved to a stepped-up category of regulation.

Based on analyses by our members, in our view, this error is the likely cause of the Federal Reserve’s projections that seven CUSO and two IHCs would be re-tiered into more stringent categories. Analyses by our members and by our consultants have not been able to recreate the elevation of CUSO and IHCs to higher tiers based on the proposed changes to the CJA indicator alone. Therefore, the error should be corrected so that such a drastic change does not happen.

3. No Tailoring Required?

The Basel Endgame proposal would generally subject all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets to the same capital requirements.15 A number of comment letters argue that this sort of approach is either flatly impermissible under, or at least inconsistent with the spirit of, Section 165 of the Dodd-Frank Act (as amended in 2018) and the tailoring approach adopted by the agencies in 2019.

These arguments have received a pretty widespread airing, including in dissenting statements from agency principals, so originally I was not planning to spend more time on anything to do with tailoring in this post.

Interestingly, though, a comment letter from a group of banking and finance scholars offers an argument that tailoring is not required:

Critics contend that the Proposed Rule violates the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act’s (EGRRCPA’s) “tailoring” mandate, which requires the Federal Reserve to “differentiate among companies on an individual basis or by category.” This claim is incorrect. The EGRRCPA’s tailoring provision applies only to “enhanced prudential standards” that the Federal Reserve issues pursuant to section 165 of the Dodd-Frank Act. The Proposed Rule, however, does not establish enhanced prudential standards pursuant to Dodd-Frank—rather, it sets minimum capital adequacy requirements as required by ILSA. Indeed, it is clear that the Proposed Rule relies on the banking agencies’ broad authority under ILSA, not the Dodd-Frank Act, because all three agencies issued the proposal jointly, whereas only the Federal Reserve has authority to establish enhanced prudential standards under Dodd-Frank. Moreover, the Proposed Rule applies to insured depository institutions that are not owned by bank holding companies, which are exempt from section 165 of Dodd-Frank. Thus, allegations that the Proposed Rule violates the EGRRCPA’s tailoring provision are inaccurate because the Proposed Rule does not rely on Dodd-Frank’s statutory authority.

The letter also goes on to argue that even assuming for the sake of argument the EGRRCPA does apply, no further differentiation between Category II, III and IV firms is required.

There are parts of this argument I am not sure about,16 but the reason I highlight it here is because the agencies in the proposal did not mention Section 165 or the EGRRCPA at all, and included only two passing references to what they now call the “regulatory tiering rule.”

Maybe that is because, like the banking and finance scholars say, Section 165, the EGRRCPA and the tailoring approach adopted in 2019 are simply not relevant here. But now that commenters have offered perspectives from both sides of the argument in their letters, I wonder if (and hope that) the Board will feel obligated in the preamble to the final rule to provide some sort of explanation as to how it currently views the constraints, if any, imposed by Section 165, as amended.

4. Minimum Denominations for Long-Term Debt — Maybe Actually a Problem

Under the long-term debt proposal, to be eligible as qualifying long-term debt the instrument in question would need to be issued in minimum denominations of $400,000. The agencies explained:

The purpose of this requirement is to limit direct investment in eligible LTD by retail investors. Significant holdings of LTD by retail investors may create a disincentive to impose losses on LTD holders, which runs contrary to the agencies’ intention that LTD holders expect to absorb losses in resolution after equity shareholders.

In a post when the proposal came out, I wrote, glibly, that this piece of the proposal, though featuring a sort of funny analytical approach from the agencies to get to the $400,000 number, seemed unlikely to result in many headaches.

As it turns out, that may have been a pretty dumb thing to write. A few commenters more informed than me believe that this would, in fact, cause a lot trouble.

For example, the Credit Roundtable, “a group of large institutional fixed income managers including investment advisors, insurance companies, pension funds, and mutual fund firms, responsible for investing more than $5 trillion of assets,” argues:

The industry standard is $2,000 minimum denomination and this is the amount the CRT recommends for external LTD requirements. Many institutional asset managers manage separate accounts (SMAs) or smaller mutual funds that may have relatively modest balances. It would not be unusual for a moderately-sized separate account for a pension fund, endowment, or trust to be in the range of $20-100 million. Similarly, a newly seeded mutual fund or ETF might have as little as $3-5 million in assets when first launched. Higher minimum bond denominations would create many problems for mandates of this size.

See also, for example, a comment letter from SIFMA making a similar point.

Thanks for reading! Thoughts on this post, including about any comments you think this post treated overly (or insufficiently) credulously, are welcome at bankregblog@gmail.com

Links to the agencies’ comment files are below.

Long-term debt: Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC.

Basel Endgame: Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC.

GSIB surcharge: Federal Reserve Board.

There are comment letters that individuals or groups have published elsewhere that are not yet posted at the links above, and there are also letters submitted to all three agencies which to this point have been posted only by one or two of the agencies. So there are likely to be more comments published at those links in the coming days.

The recaps linked in the main text skew a little toward the letters in opposition, which is fair enough because those letters do represent the majority of comments. In the interest of equal time, though, I should note (as some of the recaps do) that there were also comments filed in support of the proposal. See, for example comment letters from Anat Admati (individually), a group of banking and finance scholars (including Professor Admati and other well-known names), Better Markets, and Americans for Financial Reform.

This is obviously a subjective exercise, to which the standard caveat applies: this post makes no claim that these issues are necessarily those that are most important in the context of the proposals. They are just things I thought were interesting.

The operational risk capital requirement is then multiplied by 12.5 to arrive at risk-weighted assets for operational risk. A few commenters also criticized this part of the calculation (which is just the inverse of an assumed 8% total capital requirement), as it assumes a lower minimum capital ratio than most banking organizations as a practical matter now maintain.

For a counterargument of sorts, see the Better Markets letter:

One of the most criticized aspects of changes in operational risk measurement is the reliance on fees as an indicator of risk. However, [the Goldman 1MDB scandal] provides clear evidence that high fees may indeed be an indicator of risky behavior.

Note for example the differences of opinion in the custody bank letters from BNY Mellon, Northern Trust, and State Street as to which sort of cap they believe would be most appropriate.

Net operational losses in this context means that banks could take into account any subsequent recoveries related to the operational loss. For instance, maybe you receive an insurance payout, or an employee you catch committing fraud is forced to repay some of the money, or you accidentally send money to someone you shouldn’t have, but then get some of it back.

This is subject to a per event $20,000 de minimis threshold; events resulting in losses below that threshold don’t get counted toward the average.

In the U.S. proposal, the agencies say, “This multiplication extrapolates from average annual total net operational losses the potential for unusually large losses and, therefore, aims to ensure that a banking organization maintains sufficient capital given its operational loss history and risk profile. The constant used is consistent with the Basel III reforms.”

A footnote in the proposal explains:

The internal loss multiplier variation depends on the ratio of the product of 15 and the average annual total operational losses to the business indicator component. The 0.8 exponent applied to this ratio reduces the effect of the variation of this ratio on the internal loss multiplier. For example, a ratio of 2 becomes approximately 1.74 after application of the exponent, and a ratio of 0.5 becomes approximately 0.57 after application of the exponent. Similarly, the application of a logarithmic function further reduces the variability of the internal loss multiplier for values above 1. Taken together, these two transformations mitigate the reaction of the operational risk capital requirement to large historical operational losses.

The AORG letter says its members also thought about whether the agencies’ proposal to floor the ILM at 1 had any advantages, but members did not identify any.

The one explicit defense I’ve seen of the agencies’ proposed ILM floor comes from this Americans for Financial Reform letter, but the argument is pretty brief: “The proposal would appropriately establish a floor of 1 for the internal loss multiplier so that a firm’s lower experience of operational losses cannot drive a decline in operational risk requirements.”

IIB’s full recommendation is that the ILM should be fixed at 1 for the U.S. intermediate holding companies of foreign banks, but that if the U.S. IHC’s parent has an ILM that under capital rules in the bank’s home country is allowed to go below one, then the U.S. IHC’s ILM should also be allowed to go below one.

Northern Trust’s lead recommendation is for a fully floating ILM, but also offers the alternative that the agencies could cap the ILM at 1, while letting it float below 1.

To be clear, other banks may be (and are) subject to GSIB surcharges in their home countries, but the U.S. GSIB rule surcharge applies only to U.S.-headquartered banks.

The U.S. GSIB surcharge discussed earlier in this post is an exception, as is the eSLR.

For instance:

Are capital requirements enhanced prudential standards? It’s true that the agencies don’t typically describe them that way, but this isn’t necessarily categorical. The Federal Reserve Board, for one, in 2014 said that they were.

It is also not totally clear to me that a rule issued jointly by the agencies cannot be an enhanced prudential standard — the LCR, for instance, is a rule issued jointly by the agencies that the adopting release describes as an enhanced prudential standard. See also this report to Congress describing the LCR as such. (But see the NSFR adopting release from 2021, which tries to make more of a distinction between the LCR, NSFR and enhanced prudential standards. The release also frames the NSFR rule as being “consistent with” Section 165, without necessarily stating directly that Section 165 constrains the agencies with respect to the NSFR.)