FDIC Lays Out a Case Against Former SVB Officers and Directors

Maybe not *the* case, but *a* case

At the time that Silicon Valley Bank failed, its parent company SVB Financial Group (SVBFG) had more than $2 billion on deposit at SVB. Shortly after SVB was closed and all deposits were transferred to a bridge bank, SVBFG was able to withdraw a small portion of its deposits, but then SVBFG’s access to the deposits was halted. SVBFG’s bankruptcy estate has spent the past 22 months litigating trying to get $1.93 billion back, plus interest.

Briefly and to oversimplify, SVBFG’s primary arguments contend that the systemic risk exception invoked in March 2023 was meant to, and was consistently described by the FDIC as, protecting all deposits held by all depositors of SVB. As a result, SVBFG reasons that it, like any other SVB depositor, should get full access to its deposits.

There is a lot of procedural background and rulings in other courts that this post will skip over, but the relevant thing to know here is that in November a district court in California dismissed some of SVBFG’s claims while allowing others to proceed. Following this ruling, the FDIC1 was required to file an answer to those claims that were allowed to go forward.

The FDIC filed its answer yesterday. The answer includes a series of affirmative defenses that, for the first time, lay out in detail the FDIC’s case against former directors and officers of SVBFG and SVB. (These arguments are included in this filing because the FDIC is arguing that even if SVBFG is otherwise correct that the FDIC has unlawfully prevented SVBFG from accessing $1.93 billion that should belong to the bankruptcy estate,2 breaches of fiduciary duties by SVB’s officers and directors, allegedly aided and abetted by SVBFG, mean that the FDIC would be able to more than offset any liability it owes to SVBFG.3)

The FDIC Board of Directors voted last month to authorize the FDIC to sue six former officers and eleven former directors of Silicon Valley Bank. The answer filed on Friday is not that lawsuit. But because the allegations in the answer closely track what was described in Chair Gruenberg’s statement regarding the lawsuit authorized in December, it seems reasonable to assume that the case laid out by the FDIC on Friday includes many of the same allegations that would be included in any eventual lawsuit against the officers and directors.

The FDIC Case Against SVB’s Officers and Directors

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes below come from the affirmative defenses in the FDIC’s answer, starting at page 88.

Consistent with Chair Gruenberg’s December statement, the FDIC’s affirmative defenses laid out on Friday focus on three alleged failings by these officers and directors: (1) mismanagement of SVB’s held-to-maturity securities portfolio; (2) mismanagement of SVB’s available-for-sale securities portfolio, including by terminating certain interest rate hedges and (3) allowing SVB to pay an imprudent dividend to SVBFG. Interestingly for bank regulatory nerds, the FDIC also alleges that the three failings described above amounted to a failure by SVBFG to serve as a source of financial strength for SVB.

As background for all the below, the FDIC states that SVBFG and SVB “shared identical boards of directors, and their primary officers were the same individuals with the same roles and titles.”

Mismanagement of HTM Portfolio

The FDIC alleges that the officers and directors knew or should have known that SVB faced substantial interest rate risk and liquidity risk, yet nonetheless allowed SVB to continue to purchase long-term, fixed rate government securities and to hold those securities in its HTM portfolio which “obscure[d] losses, prevent[ed] hedging and restrict[ed] liquidity.”

For example, the FDIC describes advice given to the Finance Committee that “the duration of [SVB’s] investment portfolio should be between 3.5 to 4 years” and that “SVB’s investment strategy should aim for an allocation of 50% to 60% HTM securities (leaving 40% to 50% in the AFS portfolio).” The FDIC notes that the recommendations “tracked a plan developed by a third-party consultant, Blackrock, and were designed to manage the portfolio to enhance earnings while also reducing interest-rate risk and liquidity risks.”

The FDIC says that the officers and directors “ignored these durations” and “caused SVB’s ratio of HTM to AFS securities to increase well beyond the target of 50% to 60%.” The officers and directors allegedly did so because they wanted “SVBFG to show increased profits in the short term and attempt to boost its stock price—all at the expense of taking on and ignoring obvious and substantial risks of significant losses to SVB as interest rates rose.”

The general shape of these events is well known at this point, but the FDIC then goes on to provide more specific details about what was happening inside SVB at the time.

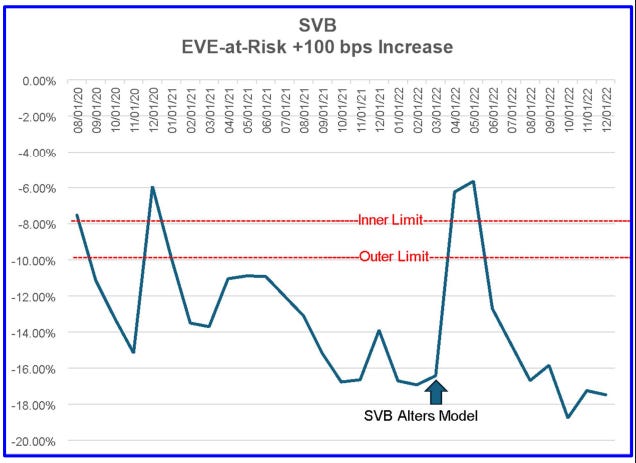

According to the FDIC’s filing, the primary metric used by SVB to assess and control interest rate risk was EVE-at-Risk - “a measure of the sensitivity to changes in interest rates of a firm’s economic value of equity.” SVB set risk limits based on EVE-at-Risk and, if those limits were breached, was required under its policies to adopt mitigation strategies.

In the case of SVBFG and SVB, their Global Treasury Policy set limits for changes in EVE-at-Risk at 8% (the inner limit) and 10% (the outer limit) in the event of a 1% change in interest rates (i.e., 100 basis points) and at 16% (the inner limit) and 20% (the outer limit) in the event of a 2% change in interest rates (i.e., 200 basis points).

If SVB breached or approached a breach of these limits, the Treasurer and Treasury Department had a responsibility to develop and present a mitigation strategy that would bring SVB back into compliance. Members of the Asset Liability Management Committee and Finance Committee (as well as the Financial Risk Management Department) had a responsibility to review and approve that mitigation strategy.

The FDIC alleges that though SVB far exceeded these risk limits its officers and directors “took no action to correct the continuous and material breaches, disregarding the risks associated with operating SVB inconsistent with its own risk policies and ignoring their responsibilities to develop and approve a plan to bring SVB into compliance with its EVE-at-Risk limits.”

Further, the FDIC alleges that rather than make changes to the HTM portfolio itself, SVB’s officers instead chose to make changes to deposit assumptions embedded in the EVE-at-Risk model. The FDIC characterizes these model changes as an attempt to “artificially lower EVE-at-Risk.”

The planning for the deposit-model change began in 2021 when members of the Asset Liability Management Committee discussed the continuous and material breaches of EVE-at-Risk and possibly changing deposit assumptions to artificially lower EVE-at-Risk.

SVBFG further enabled and facilitated this planning by hiring a consultant, Curinos, to specifically advise about these assumptions.

Following reports from Curinos and additional discussions, the Risk Committee was presented in January 2022 with a report providing for mitigation of interest-rate risk by “managing EVE sensitivity through deposit modeling.” Specifically, the report provided for altering the deposit model’s “curtailment assumption,” which was characterized as the “overall time that deposits remained with the firm.”

As reported in a May 24, 2022 presentation to the Asset Liability Management Committee, SVBFG and SVB’s officers implemented this plan by changing the curtailment assumption from 5.5 to 12 years. This change more than doubled the curtailment assumption—at a time of heightened interest-rate risk due to actual and anticipated increases in interest rates—without any valid justification for the change. Given SVB’s extraordinary deposit growth and the risky composition of those deposits, including the excessive number of uninsured deposits, SVBFG and SVB’s officers and directors knew or should have known that SVB’s deposits were inherently susceptible to leaving the bank (not “sticky”).

Ultimately, the change to the deposit model was made at [the CFO’s] insistence and without any objection from members of the Asset Liability Management Committee or the Risk Committee.

This change, which I believe was also described at a higher level in Vice Chair for Supervision Barr’s report on the supervision of SVB,4 briefly brought SVB back within its EVE-at-Risk limits, but the FDIC includes a chart (at paragraph 75) showing that this period of operating within the limits was only brief.

Termination of Interest Rate Hedges on AFS Portfolio

Next, the FDIC takes issue with a decision by the officers and directors to terminate certain interest rate swaps hedging the bank’s AFS portfolio when the officers and directors “knew the purpose of the interest-rate swaps was to help protect SVB against the risk of rising interest rates and the detrimental impact on the value of the securities portfolio.”

Again, the broad outlines of this story are well known, but this is how the FDIC describes the events.5

[The CFO] explained the rationale for the removal of the hedges in a March 17, 2022 text to [the] Director and Chair of the Boards of Directors of SVBFG and SVB and a member of the joint Finance and Risk Committees: “Just a quick head[s] up that we are unwinding today a part of our $10Bn hedging position—and selling $2Bn of Treasury securities—the rationale is that we have seen a major increase in short-term rates—and we have the opportunity to re-invest the Treasury positions at higher rates while monetizing part of our $400MM hedging gain. As a result we will recognize close to $55MM of gains on the swap unwinds and will improve net interest income by close to $19MM for the year.” (Emphasis added.)

SVBFG and SVB’s officers communicated extensively about the need for the AFS hedges and the decision to terminate them […] SVBFG and SVB’s joint Finance Committee also was kept informed of decisions to terminate and monetize the AFS interest rate hedges.

In March 2022 SVBFG and SVB’s officers and directors knew that (a) SVB had been in continuous material breach of the EVE-at-Risk limits in the Global Treasury Policy, (b) SVBFG and SVB’s senior management had forecast an increase in short-term interest rates in 2022 of at least 2%, and (c) terminating the hedges on the AFS portfolio would lengthen rather than shorten asset duration, thereby exacerbating the risk that SVB would incur significant losses as interest rates continued to rise in accordance with management’s own forecasts. Nevertheless, SVBFG and SVB’s officers and directors mismanaged SVB’s liquidity and interest-rate risk by monetizing these interest rate hedges at a time of rising interest rates to provide short-term support for SVBFG’s earnings and stock price.

The “Plundering” of SVB Through a Bank to Parent Dividend

In 2020 SVB stopped paying a dividend to its parent company SVBFG. The FDIC alleges that as late as of March 2022 the plan was for SVB to SVBFG dividends to “remain suspended through FY2023.” But after the termination of the hedges discussed above resulted in additional income to SVB, SVB’s officers and directors began to consider resuming the SVB to SVBFG dividend. The FDIC alleges that the motivation for doing so was to “increase SVBFG’s liquidity and meet its cash-flow needs” while also helping to address the “particular concern” of “[p]ropping up SVBFG’s share price.”

The FDIC contends that by taking these factors into account and ultimately approving a $294 million dividend, SVBFG’s and SVB’s officers and directors “disregard[ed] SVB’s own needs for capital, liquidity, and adequate cash flow.”

The FDIC continues:

The resumption of the bank-to-parent dividend was discussed at the October 18, 2022 Asset Liability Management Committee meeting where [the Chair of the Asset Liability Management Committee and Global Treasurer], [the CFO], and [the President of SVB] were in attendance. At that meeting, the committee approved recommending to the Finance Committee that the bank-to-parent dividend resume and that SVB pay a $294 million special dividend to SVBFG.

[The Chair of the Asset Liability Management Committee and Global Treasurer] delivered this recommendation in an October 19, 2022 memorandum to the Finance Committee. […] The October 19, 2022 memorandum reminded the Finance Committee that any dividend must “conform to State and Federal regulatory requirements,” including that the “Bank is able to maintain policy limits and thresholds on all regulatory capital ratios post-dividend,” in addition to having sufficient liquidity to meet customer needs.

Neither this memorandum nor the Finance Committee minutes or other materials reflect any analysis or discussion of whether or how SVB could meet these and other requirements. Nor did the Finance Committee document any analysis or discussion of how this dividend could be paid consistent with requirements of prudent banking and maintaining SVB’s safety and soundness.

Instead, SVBFG and SVB’s officers and directors ignored obvious and substantial risks to SVB associated with declaring this dividend. Among other things, members of the Finance Committee knew or should have known at this time that SVB had been breaching its EVE-at-Risk limits for over a year, that it was well outside those limits in an environment where interest rates were continuing to rise, that its deposit base lacked characteristics of “stickiness” that guard against deposit runs and protect liquidity, and that SVB had unrealized losses in its HTM portfolio exceeding the total value of its equity. […]

Disregarding the risks to SVB of plundering it of needed capital at a time of financial distress and management weakness, the joint Finance Committee of SVBFG and SVB approved the $294 million dividend to benefit SVBFG at the expense of SVB. A memorandum from Kruse to the Finance Committee stated that the purpose of the dividend was to help support liquidity at SVBFG. The Finance Committee’s resolution approving the dividend required that the final amount of the dividend be determined and approved by the Chief Financial Officer or Treasurer of SVBFG. […]

In addition to the members of the Finance Committee who voted to approve the dividend, the full Boards of Directors of SVBFG and SVB were notified of the intended dividend at their October 2022 combined meeting. […] The minutes do not reflect any objection or other opposition to the dividend by these joint directors of SVBFG and SVB.

The SVB to SVBFG dividend was approved in October but was not due to be paid until December. The FDIC suggests that, as SVB’s condition continued to worsen in that period, the officers and directors could have walked back their decision to pay the dividend, but chose not to do so.

At the December 16, 2022 Risk Committee meeting, management advised the committee members that “market and liquidity risk profiles had increased materially over 2022, causing a deterioration of the Company’s liquidity and market status, as evidenced by internal liquidity stress testing, resulting in [the Financial Risk Management Department] raising the risk profile rating to ‘high’ for both market and liquidity risk.” […] Despite the worsening financial conditions of SVB, there was no effort by any of the directors to reverse the decision to make the bank-to-parent dividend payment.

Similarly, senior management made no effort to stop the bank-to-parent dividend and instead reaffirmed the decision to pay the dividend. For example, a December 21, 2022 presentation to the Finance Committee highlighted that SVB remained in breach of its liquidity metrics: “With higher than forecast deposit outflows, we have breached our Net Liquidity Position (NLP) metric. How do we stabilize our funding and mitigate our NLP breach?” Nonetheless, [the CFO] replied that he was “good” with paying the dividend and had it paid out to SVBFG at the end of December.

The FDIC closes this portion of its allegations by noting that in January 2023 the Finance Committee approved a further $200 million SVB to SVBFG dividend, but SVB failed before that dividend could be paid out.

Source of Strength

After laying out the allegations described above, the FDIC in paragraphs 109-114 of the affirmative defenses discusses the obligation of a bank holding company to serve as a source of strength to its depository institution subsidiary.

After citing to Regulation Y, a 1987 Federal Reserve Board policy statement, and the statutory source of strength obligation adopted as part of the Dodd-Frank Act,6 the FDIC argues that the officers and directors of SVBFG and SVB, through the failings described above, “ignored obvious and substantial risks of loss to SVB to provide benefits to SVBFG.” These actions, the FDIC alleges, amounted to a breach of “SVBFG’s basic responsibility to act as a source of strength for SVB.”

***

Under a schedule agreed by the parties, a response of some kind by SVBFG to the FDIC’s answer is due by February 14.

This post will keep things simple by referring to the FDIC, but technically the case is being litigated by SVBFG against the “FDIC-Rs” - that is, the FDIC in its capacity as receiver for SVB (“FDIC-R1”) and the FDIC in its capacity as receiver for Silicon Valley Bridge Bank (“FDIC-R2”).

To be clear, the FDIC in no way concedes this, as demonstrated throughout the nearly 90 pages of the answer before getting to the affirmative defenses.

In addition to these setoff rights, the FDIC also throws in equitable defenses like unclean hands and unjust enrichment.

See page 63 of the Barr report:

In response to EVE breaches, SVBFG made model changes that reduced the level of risk depicted by the model. In similar fashion to the response to liquidity shortfalls, management changed assumptions rather than the balance sheet to alter reported risks. In April 2022, SVBFG made a poorly supported change in assumption to increase the duration of its deposits based on a deposit study conducted by a consultant and in-house analysis. Under the internal models in use, the change reduced the mismatch of durations between assets and liabilities and gave the appearance of reduced IRR; however, no risk had been taken off the balance sheet. The assumptions were unsubstantiated given recent deposit growth, lack of historical data, rapid increases in rates that shorten deposit duration, and the uniqueness of SVBFG’s client base.

The emphasis in the below paragraph (and the note saying that emphasis was added) comes from the FDIC, not from me.

The FDIC does not cite to the source of strength regulations that the federal banking agencies were required by statute to adopt. This is because those regulations, more than a decade after the deadline for them, do not exist.