Catching Up

Rakuten's ILC application, Hurry v. FDIC, are syndicated loans securities, a notable claim about the FHLB Dallas, and another Canadian bank (maybe) having merger problems

This post features brief comments on a few of things I came across over the past two weeks that I thought were interesting, some of them genuinely newsworthy, others of them probably not so much.

Rakuten Withdraws Deposit Insurance Application, Again

Rakuten, “the largest eCommerce marketplace in Japan and the third-largest eCommerce marketplace globally,” applied in July 2019 to charter a new Utah industrial bank and applied to the FDIC for deposit insurance. That application to the FDIC was withdrawn in March 2020, but at the time it withdrew Rakuten said it would re-file and the company did so in late May 2020.

Rakuten’s second application sat with the FDIC for just under two months and then was again withdrawn by Rakuten in July 2020.

In January 2021, Rakuten tried again, filing an application for deposit insurance with the FDIC for the third time. The FDIC’s monthly applications update, released yesterday afternoon and current through the end of May 2023, shows that on May 30 Rakuten withdrew its application for the third time.1

From what I can tell, Rakuten to this point has not made a public statement regarding this third withdrawal, and it is not clear if they intend to try again or if this is the end for their U.S. ILC plans, at least for now.

The Rakuten withdrawal means there are now four ILC-related applications still pending with the FDIC:

GM Financial Bank (new bank): application filed December 2020; no updates since

Thrivent Bank (new bank): application filed February 2021; withdrawn April 2021; re-filed July 2021; no updates since

Ameriprise Bank (conversion of federal savings bank to industrial bank): application filed June 2021; “accepted” November 2022; no updates since

Ford Credit Bank (new bank): application filed July 2022; no updates since

In a post last year I wrote that “at some point the time-honored FDIC tradition of simply ignoring industrial bank applications in the hope that they will go away is going to prove untenable,” but I may have underestimated the FDIC’s power of will.

Controlling The Bank of Orrick

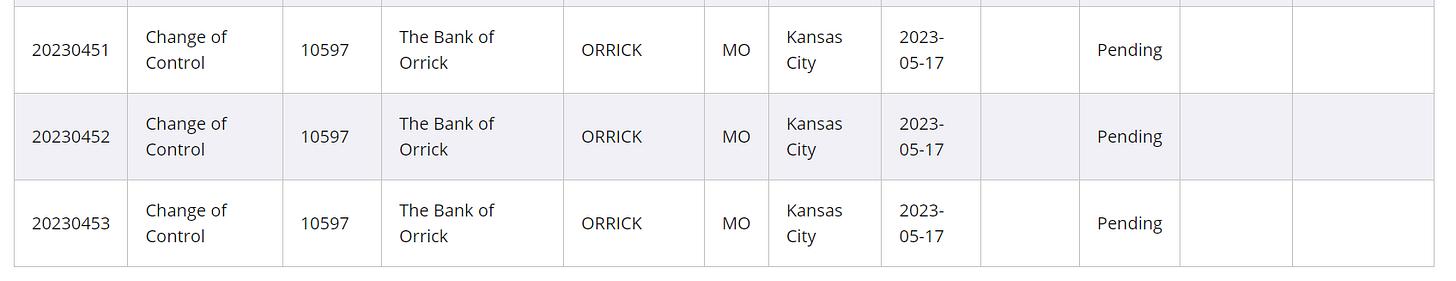

Another semi-interesting thing in the FDIC’s applications update yesterday was the news that in mid-May a change of control application was filed concerning the Bank of Orrick.

The Bank of Orrick is a $59 million asset Missouri bank whose name might not be immediately familiar, but this is the bank that was the subject of the Change in Bank Control Act application in the Hurry v. FDIC case last year.

There, a federal district court in Washington, DC, ruled that the FDIC had improperly delayed taking action on a CIBC Act application by Justine Hurry, and that it was time for the FDIC to do something, one way or the other.2

The unlawful agency actions in this case are the FDIC’s decisions returning Hurry’s March 13, 2018 notice as “incomplete” and then closing her file on grounds of abandonment, and nothing in Allied-Signal or the APA counsels against setting those decisions aside. … Setting those decisions aside, however, does not mean that Hurry may proceed with the proposed acquisition. It just means that the FDIC must now treat the notice as properly filed and, within the statutory period, either disapprove the acquisition or allow it to proceed.

Hurry was decided in February 2022. The FDIC in late May 2022 acted on the application, issuing a rare on-the-record denial.

Now, though, someone (or a group of someones) is trying again.

The FDIC’s update yesterday does not provide further details on which persons or entities are behind the newly filed applications.

Are Syndicated Loans Securities? Also, the Edge Act

In May 2020 the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled that syndicated term loans for which JPMorgan Chase and other large banks acted as arrangers were not securities under the federal securities laws. The case is now on appeal before the Second Circuit, and oral argument was held back in March.

I realize that all is old news, but a thread from Professor Ann Lipton this week clued me in to a few things about the case I did not know or had forgotten.

First, the SEC has been invited by the court to by June 27 put forward “any views [it] may wish to share on this issue.” The SEC, as more and more companies are learning, is somewhat prone to thinking things are securities, but it would be pretty remarkable for them to take that position here.3 On the other hand, remarkable things do happen from time to time, and there is a 1992 Second Circuit precedent relevant to this case, Banco Español, the conclusions of which the SEC may not fully endorse,4 so the Commission may try to thread the needle a bit.

Relatedly, JPM asked the Second Circuit, so long as the court was soliciting views from the SEC, to also see what Treasury, the Federal Reserve Board, FDIC and OCC had to say on the matter. The panel was either not interested or did not think this was necessary.

Finally, a Second Circuit decision on this case may also feature a ruling on what is now Section 25B of the Federal Reserve Act (12 USC 632).5 This is a provision saying that civil suits to which any corporation organized under the laws of the United States is a party and that, among other things, “aris[e] out of transactions involving international or foreign banking,” or “other international or foreign financial operations” may be removed from state court to federal court.

JPM’s position here is that because “Kirschner himself admits that Edge Act bank JPMorgan Bank ‘directly transacted with’ hundreds of foreign lenders and two foreign fund managers to syndicate the term loan that is at the center of this case,” 12 USC 632 applies and removal was proper. Kirschner disagrees, arguing that the recapitalization transaction at issue was actually “wholly domestic” and that the “mere presence” of a foreign bank does not mean that 12 USC 632 removal is available.6

From oral argument it sounded to me like the panel (Judges Cabranes, Bianco, and Pérez) thought JPM had the better of the argument, both on the securities law question and the removal question, but this is always a risky basis on which to make predictions.

Federal Home Loan Banks as the Lender of Last Resort

Last week the FDIC held a periodic meeting of its Advisory Committee on Community Banking. During the portion of the meeting on asset liability management, there was the following exchange:7

Rae-Ann Miller, FDIC Senior Deputy Director, Division of Risk Management Supervision: I can tell you from experience that having your securities at the Federal Home Loan Bank is helpful, but having a plan that if you need to quickly get them to the Fed — the Federal Home Loan Bank is not the lender of last resort, so if you need that, setting that up ahead of time is crucial. […]

Troy Richards, President, Guaranty Bank & Trust Company, Delhi, Louisiana: You might be interested to know that our CEO is on the board of FHLB Dallas and they were recently told some information — from FHLB — that FHLB considers themselves to be lender of last resort. So what is that going to mean for us going forward? […]

Rae-Ann Miller: Yeah, I hadn’t heard that, but we can certainly look into that.

Of course the most likely thing here is that something got a little garbled as it passed from person to person and, even if this is what said, this is (I hope!) not what this unnamed person at the FHLB Dallas meant. But as Mr. Richards said, it was indeed something that I might be interested to know.

Another Bank Merger Slowed Down

This blog has written a few times about the approach a some companies have taken, or are trying to take, to obtain a U.S. bank charter by acquiring a small U.S. bank.

One company in this category is VersaBank, which last summer announced a deal to acquire Stearns Bank Holdingford, a Minnesota-based national bank with around $78 million in total assets at the end of Q1 2023. The twist here though is that, unlike other recent fintech acquirers seeking to enter the U.S. banking system by buying a nice tidy little bank, VersaBank is already chartered as a bank in its home country of Canada.

As shown by a series of VersaBank updates since last June, the application process has not progressed as quickly as initially planned:

June 14, 2022: “Closing of the acquisition, expected before the end of VersaBank's fiscal year (October 31, 2022)...”

August 31, 2022: “The transaction is anticipated to close before December 31, 2022...”

December 7, 2022: “The transaction is anticipated to close in the first half of calendar 2023”

March 8, 2023: “VersaBank anticipates receiving a decision with respect to approval of the proposed application from US regulators during the second calendar quarter of 2023 and, if favourable, will proceed to complete the acquisition as soon as possible...”

June 7, 2023: “The Bank continues to advance the process seeking approval of its proposed acquisition of OCC-chartered US bank, Stearns Bank Holdingford, and expects a decision with respect to approval of its application from US regulators by the end of summer 2023”

This timeline, though dragging on longer than VersaBank originally hoped, is not yet dramatically out of keeping with the timeline for a few other recent small bank acquisitions by acquirers without a U.S. bank charter.8 Add in the fact that there are extra wrinkles that come when a foreign bank is trying to make a U.S. bank acquisition, and on its face it is not completely surprising that things are taking this long. So although I have no particular insight into what is going on behind the scenes, my guess is that everything is going to work out okay for VersaBank in the end.

Even so, it does not reflect very well on the bank merger review process, regardless of your preference as to the ultimate outcome, that parties’ expectations can so significantly diverge from the timelines of the agencies, often for reasons that are never publicly explained.9 If you are concerned about the public’s trust in banking and bank supervision, you might regard this as suboptimal.

Look out tomorrow for another post like this one with brief thoughts on a grab bag of recent developments. In the meantime, thoughts, challenges or criticisms are always welcome at bankregblog@gmail.com.

Rakuten’s application to the Utah DFI was withdrawn on the same day.

As JPM and its amici point out, the syndicated loan market is a 2.5 trillion dollar market. On the other hand, as Kirschner and its amici point out, the syndicated loan market is a 2.5 trillion dollar market.

Here is an amicus brief from Americans for Financial Reform calling for Banco Español to be overruled and the district court’s ruling in this case to be reversed. See in particular pages 26-28 for a discussion of the position the SEC took thirty years ago in Banco Español.

As AFR acknowledges, this is an “aggressive argument” because it would require the three judge panel to exercise the Second Circuit’s “mini-en banc” power. Also, a footnote in AFR’s brief “candidly acknowledges the Court isn’t necessarily required to consider this argument. Normally, an amicus brief is ‘not a method for injecting new issues into an appeal, at least in cases where the parties are competently represented by counsel.’ [citing cases] And this is a high-stakes appeal in which the parties’ representation isn’t merely competent, but fabulous.” Even so, AFR says that because “the parties have already briefed the implications of Reves, Banco Español, and Pollack extensively” the question of “whether Banco Español should be overruled is merely an elaboration of the parties’ existing arguments.”

Equal time: see this amicus brief from a group of trade associations supporting the district court’s decision and saying that the Second Circuit’s reasoning in Banco Español “applies equally to syndicated term loans like that here.”

This provision was added to the original 1919 Edge Act by a provision of the Banking Act of 1933 and in this case and elsewhere courts have referred to 12 USC 632 simply as the Edge Act and banks like JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. and, in a previous case, Bank of America, N.A. as “Edge Act banks.” I’ve tried to avoid that usage here because while I understand where it is coming from I find it a little confusing.

I am committing what is one of my biggest pet peeves here when I see it done by others: writing about a court case and not linking to the briefs/opinion. But I cannot find free versions of the parties briefs online. For what it’s worth (ten cents a page), the PACER link to the docket is here.

Obviously these are not perfect comparisons, but SoFi’s acquisition of Golden Pacific Bank took about a year from signing to closing, as did LendingClub’s acquisition of Radius Bank.

To be fair to the U.S. banking regulators, per VersaBank’s latest press release the transaction also is yet to be approved by OSFI in Canada.