It has already been quite a busy year for U.S. bank regulation, but as everyone gets set to return to work this week following today’s Labor Day holiday this post looks at ten areas where there could be further noteworthy developments before the end of the year.

Stress Testing and Stress Capital Buffer

Federal Reserve Board Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr has on a few occasions spoken about his desire to continue to refine the Board’s supervisory stress test and the stress capital buffer framework. For example, and consistent with prior remarks, in a July speech the Vice Chair for Supervision stated:

Fourteen years of stress testing, and the real-life surprises during that time, including the pandemic and the bank stresses this spring, have made it clear that stress tests need to be stressful to adequately prepare banks for unanticipated events. A key strength of stress testing is its ability to be responsive to the rapidly changing conditions by testing bank resilience to emerging or growing risks. In addition, stress testing can be used to assess banks' resilience to different kinds of stress in the financial system. For example, we have long known—and the recent experience with SVB reinforced—the importance of banks' resilience to funding stress.

The stress test should evolve to better capture the range of salient risks that banks face. In addition, the Board could use a range of exploratory scenarios to assess banks' resilience to an evolving set of risks and use the results to inform supervision.

If not before then, a preview of what VCS Barr has in mind for next steps on the supervisory stress test may come in mid-October at the Federal Reserve’s 2023 Stress Testing Research Conference, at which he is scheduled to give the keynote address.

Inspector General Reports

In the few months following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, a number of reports were released. Reports on SVB were produced by Federal Reserve Board Vice Chair for Supervision Barr and the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation. Reports on Signature Bank were produced by the FDIC’s Chief Risk Officer and the New York State Department of Financial Services. In addition, the Government Accountability Office issued a preliminary review touching on the failures of both SVB and Signature.

Before the end of the year at least two more (and possibly up to four) reports are expected to be released.

The Federal Reserve Board’s Inspector General has stated that it is conducting a review into the supervision of SVB. This report is being treated as a material loss review. Publication is expected by the end of September.

The Board’s Inspector General has also announced that is conducting a review of the supervision by the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco of Silvergate Bank, the California-based bank that earlier this year announced plans to voluntarily liquidate.1 This report is also expected by the end of September.

The FDIC’s Inspector General is conducting a material loss review regarding Signature Bank. The FDIC IG has not provided an expected date for publication of this report.2

The FDIC’s Inspector General is also a conducting a material loss review regarding First Republic Bank. The FDIC IG has not provided an expected date for publication of this report.3

As noted above, three of the upcoming reports are material loss reviews. The background to this is that if the Deposit Insurance Fund suffers a “material loss” with respect to an insured depository institution,4 Section 38(k) of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act requires the inspector general of the banking agency responsible for the supervision of the failed bank in question to prepare a written report into the institution’s failure.

The written report must (1) “ascertain why the institution’s problems resulted in a material loss to the DIF” and (2) make recommendations for preventing such losses in the future.

Changes in Federal Reserve Supervisory Approach

The underlying reasons for this are open to debate, but a generally undisputed theme in the already-released reports described above has been slow action by supervisors, reluctance to escalate issues and, in some cases, failure to focus on the right issues.

Efforts are ongoing to fix this. Bloomberg reported last week, for example, on ramped up issuance of MRIAs and MRAs by the Federal Reserve. As Bloomberg noted in the story, the issuance of MRIAs and MRAs is not itself unusual, but as a lawyer quoted in the story hinted at, the time being given to banking organizations to resolve these supervisory findings is also an area where supervisory expectations have grown more intense.

“The bigger concern is the time frame we’re talking about for resolution,” said Gary Bronstein, who leads the financial-services team at the law firm Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP. “We’re going to start seeing the supervisory staff impose tight deadlines on resolution. If banks are not resolving these issues pretty quickly, then we’ll see enforcement actions.”

Later this year we may get to see some more concrete data on this. It has been the Board’s practice in the November versions of its semi-annual supervision and regulation reports to provide data on (1) how many firms with $100 billion or more in total assets are in unsatisfactory condition and (2) how many supervisory findings remain outstanding.

There are limitations in this data,5 including that it is initially reported as of the end of Q2 and so by the time the report is published in November comes with a lag, but even so it could be helpful in quantifying the change in supervisory approach. As reminder, here is what last year’s data showed:6

Ratings for large financial institutions

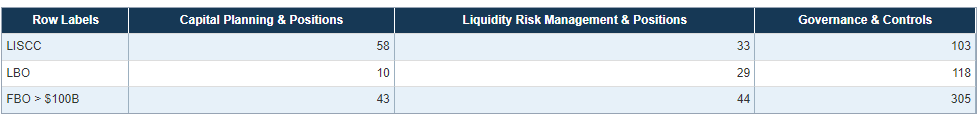

Outstanding number of supervisory findings, large financial institutions

Outstanding supervisory findings by category, large financial institutions

On that last chart, one thing also worth watching is whether there is an increase in findings on capital and liquidity relative to governance and controls. Per the VCS Barr report on SVB, at the time of its failure SVB Financial Group had 31 open supervisory findings, 20 of them relating to governance and controls. The firm’s governance and controls rating was Deficient-1, while its ratings for capital and liquidity were passable (Broadly Meets Expectations and Conditionally Meets Expectations, respectively). The Barr report says, understatedly, that these ratings “did not fully reflect the vulnerabilities of SVBFG.”

Supervisory Culture Review

Separately from but related to the above, Vice Chair for Supervision Barr in June said that he was working on a broader project relating to the Board’s supervisory approach. The American Banker reported at the time:

“Over the next six months, we're going to do a project that looks systemwide at the areas where we can enhance our supervisory culture, our practices, our behaviors, ours tools and also where we need to change our regulation of firms," Barr said at the event, which was hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. "We're extremely focused on that."

It is not clear what the public output of this project, if any, will be.

Climate-Related Financial Risk

Domestically

The Federal Reserve Board is in the process of reviewing information submitted to it on or before July 31, 2023 by six U.S. GSIBs as part of the Board’s Pilot Climate Scenario Analysis Exercise. Aggregate results and other insights gained are expected to be published “around the end of 2023.”7

The agencies are also working to finalize their guidance on climate-related financial risk management.

Internationally

At the international level, the Basel Committee by the end of the year intends to issue a consultation paper on a Pillar 3 disclosure framework for climate-related financial risk.

In addition, though the precise date for these actions is not yet clear and so they may not happen by the end of the year, Basel Committee leadership also has said that the Committee intends to:

As part of its efforts to assess potential material gaps in the Basel framework, “consider whether potential regulatory measures to address climate-related financial risks are needed”;

“monitor the implementation of its Principles for the effective management and supervision of climate-related financial risks”; and

“discuss potential complementary work related to banks’ transition planning and the use of climate scenario analyses.”

Perhaps only tangentially related to the above, but on the subject of climate this speech today from Frank Elderson, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB and Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, included some pretty striking statements.

Liquidity Regulation

In terms of concrete regulatory proposals following the bank failures of earlier this year, changes to the regulatory liquidity framework have to this point taken a back seat to capital and long-term debt proposals.

In the cover letter accompanying his report on the supervision of SVB, Vice Chair for Supervision Barr wrote:

In addition, we are also going to evaluate how we supervise and regulate liquidity risk, starting with the risks of uninsured deposits. Liquidity requirements and models used by both banks and supervisors should better capture the liquidity risk of a firm’s uninsured deposit base. For instance, we should re-evaluate the stability of uninsured deposits and the treatment of held to maturity securities in our standardized liquidity rules and in a firm’s internal liquidity stress tests.

The details matter a lot of course, but changes to liquidity rules, in theory, could have comparatively greater buy-in from GOP appointees at the U.S. banking regulators than did the agencies’ capital-related proposals earlier this summer.

In a speech in May, for example, Federal Reserve Governor Bowman stated, “I expect that we will find improvements to supervision, revisions to liquidity requirements, or improvements to bank preparedness to access liquidity are more effective than increases in capital for a broad set of banks.”

This may, however, be an area where the immediate next step may not be a proposed rule by the U.S. banking regulators, but rather some sort of more preliminary consultation. Also potentially arguing in favor of this sort of consultative approach is that international regulators too have signaled that they believe another look at the design of liquidity regulation would be appropriate. For example:

In a speech in April, the Chair of the Basel Committee noted that the Basel LCR had initially included “relatively conservative outflow factors,” but in light of “stakeholder input” that highlighted the “perceived overly conservative nature of the proposals and the role of banks’ own risk management practices” those outflow factors were revised in the final standard.8

In a June press release, the Basel Committee said that, building on initiatives already underway, it intended to examine the regulatory implications of the stresses earlier this year, including with respect to liquidity risk management.

In a speech in late August, Claudia Buch (reported by Reuters in early July to be the frontrunner for the next chair of the Single Supervisory Board) set out these “priorities for a structured review of liquidity requirements”:

“banks must be able to liquidate [HQLAs] immediately and at any time”;

“relevant liquidity indicators, including the concentration of funding sources, could be monitored more frequently”; and

“it needs to be assessed whether assumptions on the stability of deposits adequately reflect effects of social media and new digital banking services.”

All the above goes to the question of how liquidity rules should work. In the United States a related live topic is the issue of to whom the rules should apply. In particular, even if revisions to the how aspects of the rule will take some time to get ready, it is possible the agencies will separately and more quickly seek to expand the LCR and NSFR to Category IV firms, most of which are not currently subject to these rules.

On this point, in the cover letter to his report on SVB, VCS Barr said that the Board should “consider applying standardized liquidity requirements to a broader set of firms.” Given how this question was answered recently with respect to the proposed application of the revised capital rules and the newly proposed long-term debt requirement, Category IV firms likely have an idea as to what the answer will be.

If Category IV firms are in fact going to be subject to LCR and NSFR requirements this raises the further question of how those requirements should be calibrated. Specifically, would the agencies retain the concepts of “reduced” LCR and NSFR requirements of 85% (for certain Category III firms) or 70% (for certain category IV firms), or would they instead conclude that all firms above $100 billion in total assets, regardless of category, should be subject to 100% LCR requirements? Again the proposals of late July and late August seem to hint at an answer.

Capital Rules Proposal — November 30 Comment Deadline

The U.S. banking regulators have set November 30 as the comment deadline for (i) the capital rule changes proposed in late July, (ii) the long-term debt proposal released last week, (iii) the proposed resolution planning guidance for Triennial Full Filers released last week and (iv) the FDIC IDI plan rule changes released last week.

When the capital proposals were released in July, agency principals made sure to highlight the relatively lengthy comment period they were adopting, which was in line with requests made by trade groups:

Chair Powell: “I am confident that, for the proposals before us today, the process will also be a transparent, deliberative and thoughtful one, and in that spirit I welcome the 120-day comment period.”

Vice Chair for Supervision Barr: “The extended 120-day comment period is appropriate and will allow all parties adequate time to fully analyze the issues presented in the rule.”

FDIC Chairman Gruenberg: “Given the consequence and complexity of this rulemaking, the agencies are providing a 120-day public comment period.”

Some banks may now feel that the agencies’ generosity in providing 120 days for comment has been oversold, now that it has been revealed that three other significant proposals must also be reviewed and commented on by that deadline. We’ll see whether the November 30 date holds up for all proposals, or whether the comment period for at least some of them will be further extended.

Capital Rules Proposal — Will Congress do Anything Interesting?

Possibly of more importance is the return by Congress this week (Senate) or next week (House) from its summer break. In July, House Financial Services Committee Chairman promised “significant oversight” in relation to the agencies’ capital rules proposals, and Politico reported it was likely that the HFSC would hold hearings into the matter.

Some of this can be chalked up to bluster, and I obviously have my own biases, but I do not think it is overstating the case to say that there is heightened bipartisan interest in what the agencies are doing with the capital rules proposals and why.

For example, in early July, Representatives Andy Barr (frequently combative) and Bill Foster (usually not) sent a bipartisan letter to Vice Chair for Supervision Barr asking that, before the Federal Reserve Board released any proposed rules, Vice Chair for Supervision Barr first provide “details of your holistic review, Basel III reform plans, and testimony before our Subcommittee.” The letter also requested a response “as soon as possible, but no later than 60 days before your public notice of the Basel III proposed rule and/or the holistic capital review.” Of course, none of this happened.

Add in the proposed changes relating to the risk weights that would need to be assigned to certain mortgages, which critics say could have negative effects on availability of credit for first time or minority borrowers, and there is plenty of stuff for Congress to take a cross-party interest in, should they be inclined to do so.

Community Reinvestment Act

The agencies have been working to finalize a Community Reinvestment Act rule for a while now. A final rule could be released sometime before the end of the year, although bank trade groups a couple weeks ago requested that the agencies instead hold off until (1) the capital rule changes are finalized and (2) there is clarity from the courts as to the constitutionality of the CFPB and the legality of the CFPB’s rule requiring banks to collect data on small business lending, which would be an input to certain aspects of the CRA rule.

Resolution Planning

The Federal Reserve Board and FDIC issued a series of resolution planning-related proposals last week, but one change not yet proposed is an extension of holding company resolution planning requirements to U.S. Category IV firms (mostly regional banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in total assets).

Making Category IV firms again subject to resolution planning requirement was an explicit recommendation of the Biden Administration and an implicit recommendation of the VCS Barr report.9 It would not be surprising to see action on this at some point as well, although the incremental benefit may be relatively small if the FDIC’s IDI plan is finalized in something close to the ambitious version in which it was proposed.

Miscellaneous FDIC Agenda Items

Finally, as always it is important not to take the banking agencies’ regulatory agendas too seriously, but I am still curious about these two FDIC agenda items from a few months ago, as we have not heard much (if anything) about them since then.

Parent Companies of Industrial Banks

The FDIC will request comment on a proposal to amend the existing FDIC regulation of the same name at part 354 to reflect supervisory experience. The proposed amendments would revise the scope of the regulation, clarify the role of written commitments, and set forth additional criteria that the FDIC would consider when reviewing filings.

I have no idea if the FDIC intends to ever act on the industrial bank deposit insurance applications that are still pending (from GM, Ford and Thrivent as of this writing), but if the FDIC does have plans to do so, proposing whatever the above is describing may be a prerequisite to that.

Consent to engage in covered activities

The FDIC again:

The FDIC is seeking comment on proposed amendments to its regulations to establish filing requirements for FDIC-supervised institutions that seek to engage in certain covered activities, including permissible crypto-related activities and plans to leverage technological innovations to augment and transform the delivery channels through which they provide banking services.

The agency previously said it was targeting September 2023 for this rulemaking.

Thanks for reading! I am sure I left out some crypto-related stuff. Let me know what else I missed at bankregblog@gmail.com

I am not sure if this is part of the workplan, but it would be interesting for this IG report to also address what happened behind the scenes earlier this summer such that the Board and DFPI determined that Silvergate could not be left to its own devices and that an enforcement action was necessary to make sure Silvergate proceeded appropriately with its previously announced liquidation.

The FDI Act requires that material loss reviews be completed within six months. The wrinkle, though, is that this is not necessarily six months from the date of failure. The statute says the six-month period begins “on the date on which it becomes apparent that the present value of the outlays of the Deposit Insurance Fund with respect to that institution will exceed the present value of receivership dividends or other payments on the claims held by the Corporation.”

Obviously given the size of these bank failures the certainty of a material loss to the DIF has been apparent from the very moment they failed, but I am not positive the clock began for material loss review purposes on that date. See, e.g., this May 17, 2023 testimony from the Federal Reserve Board’s Inspector General, saying that it had “last week” received notice from the FDIC of the estimated loss to the DIF from the failure of SVB two months earlier, and so technically its deadline for a material loss review is November 2023, but that “[n]evertheless, we plan to issue our report in September 2023.”

See note 2.

Material loss generally means a loss in excess of $50 million.

Another limitation is that starting in 2019 the Board began to evaluate firms with $100 billion or more in total assets under the Large Financial Institutions rating system. Prior to this, and as is still currently the case for holding companies with less than $100 billion in total assets, firms were evaluated under the old RFI/C(D) system. This means that the pre-2019 and post 2019 ratings are not directly comparable. (It also means, I think, that the header row in the table in Figure 9 is wrong - the rating scale for LFIs is no longer 1-5.)

The data comes from the accessible versions of Figures 9, 10 and 11 located here which, unlike the versions in the PDF copy of the report, break out the numbers and percentages.

No firm-specific information will be published.

The Board expects to disclose aggregated information about how large banking organizations are incorporating climate-related financial risks into their existing risk-management frameworks. Consistent with the objectives and design of the pilot exercise, the Board does not plan to disclose quantitative estimates of potential losses resulting from the scenarios included in the pilot exercise. No firm-specific information will be released.

See footnote 15 in the remarks: “For example, the outflow rates for core funding sources such as corporate and retail deposits were set at 75% and 7.5–15%, respectively. The lobbying pushback and assertions of ungrounded calibrations resulted in a dilution of these outflow rates to 40% and 3–10%.”

See, e.g., page 91: “In the absence of these changes, SVBFG would have been subject to enhanced liquidity risk management requirements, full standardized liquidity requirements (i.e., LCR and NSFR), enhanced capital requirements, company-run stress testing, supervisory stress testing at an earlier date, and tailored resolution planning requirements. These requirements may have resulted in SVBFG’s having increased capital and liquidity that would have bolstered its resilience.” (emphasis added).